Go to Part 1

This is the point where we take all of the procedures we’ve discussed up to this point and put them into practice in order to generate a dungeon key.

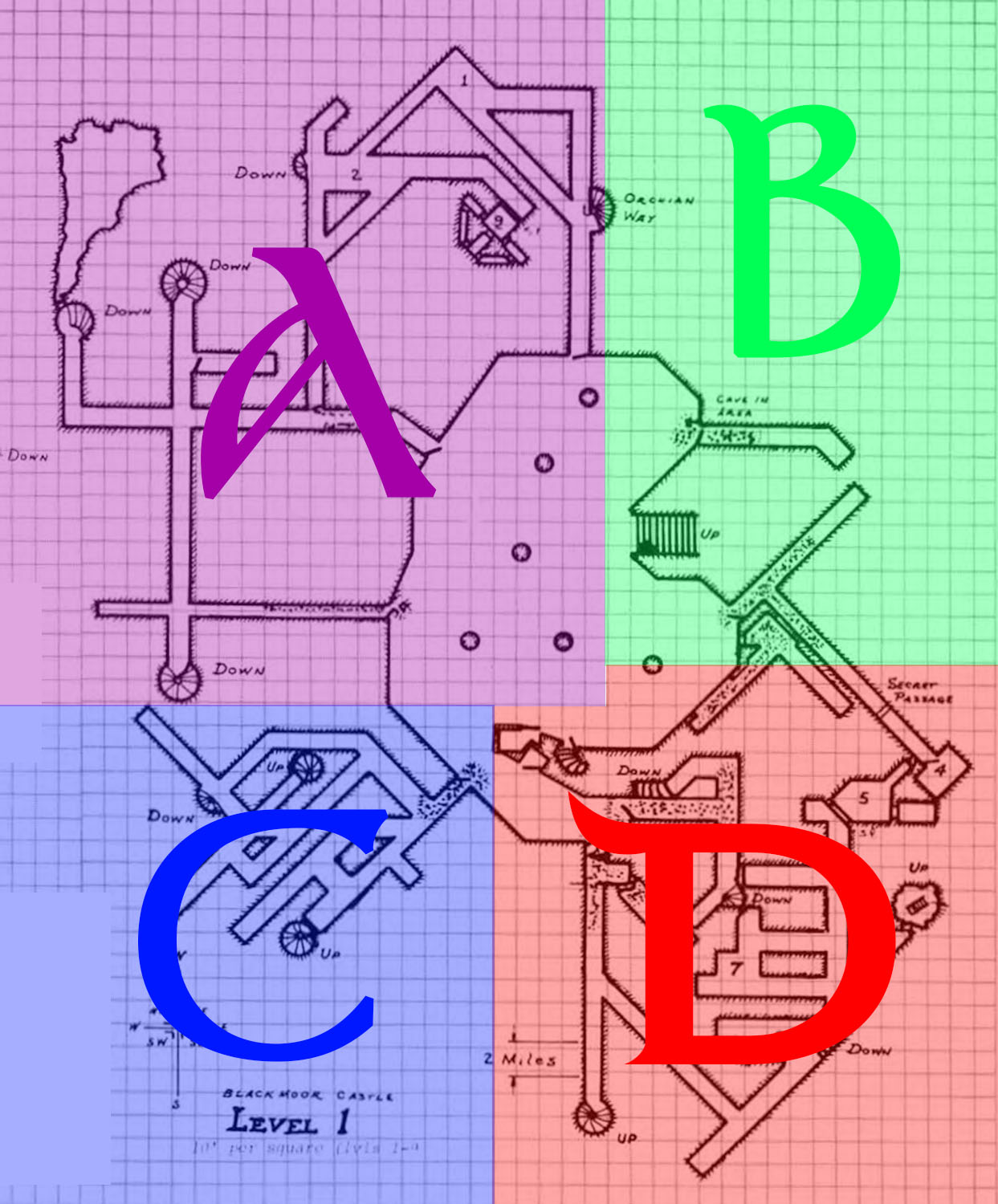

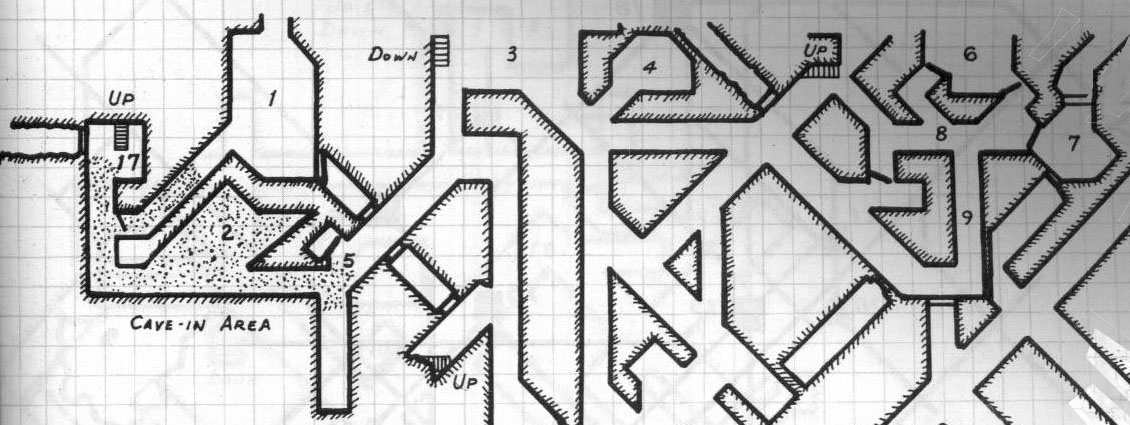

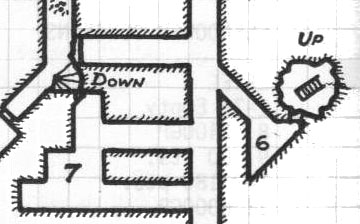

In order to make full use of this material, you’ll need copies of the Blackmoor Dungeon maps. The maps from the First Fantasy Campaign are ideal, but those from Zeitgeist Games’ Dungeons of Castle Blackmoor are adequate, despite introducing a number of new errors. (The most notable of which was that the cartographer didn’t understand how Arneson indicated secret doors on his maps, so missed several of them and turned the rest into normal doors.) The Zeitgeist Games release does have the advantage of currently being available on DriveThruRPG.

Even without the Blackmoor maps, however, it should be noted that these procedures can be used with any dungeon (particularly those designed along megadungeon lines), even one of your own! So you could grab Undermountain or the Castle of the Mad Archmage or Rappan Athuk and go to town. Or pull out the graph paper and get to work. You wouldn’t be the first, but you would join the same heady tradition as Greg Svenson’s Tonisborg, Richard Snider’s Baronies, and Gygax’s Greyhawk.

There are four versions of the key available for download as Microsoft Word files:

Blank Template – Glendower Template – Seed 1 – Seed 2

COLLECTED ZIP FILE

THE KEYS

BLANK TEMPLATE: This file is a blank template for stocking the dungeons of Castle Blackmoor. It includes the first seven levels, with a table including spots for Protection Points, Creatures, and Treasure/Notes. When I stocked the dungeon, I did three passes:

- Check each room for habitation and, if so, generate Protection Points.

- Go back to each room with a Protection Point budget and generate creatures.

- Make treasure tests for all of the rooms.

It stops at Level 7 because that’s where Arneson’s guidance for protection point budgets stopped. I’m not certain whether it makes more sense to continue increasing the point values at higher levels or allow them to plateau at 50 x 1d10, and I figured putting the current material into play might help elucidate the matter. (So we’ll see where that leads us the in future.)

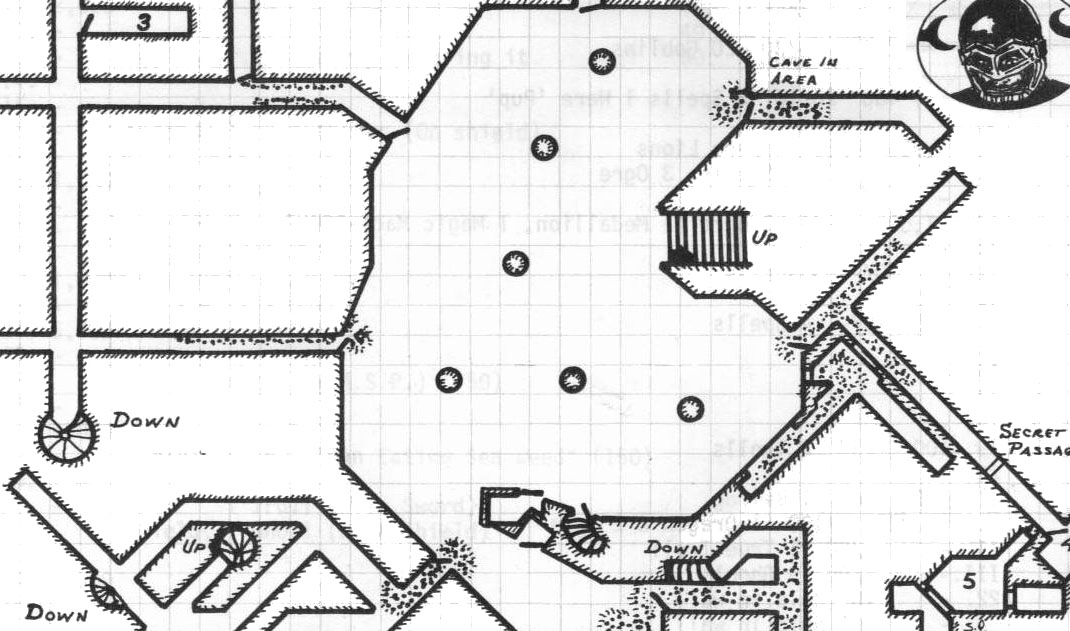

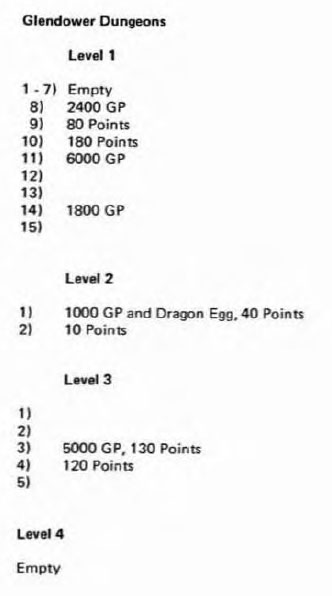

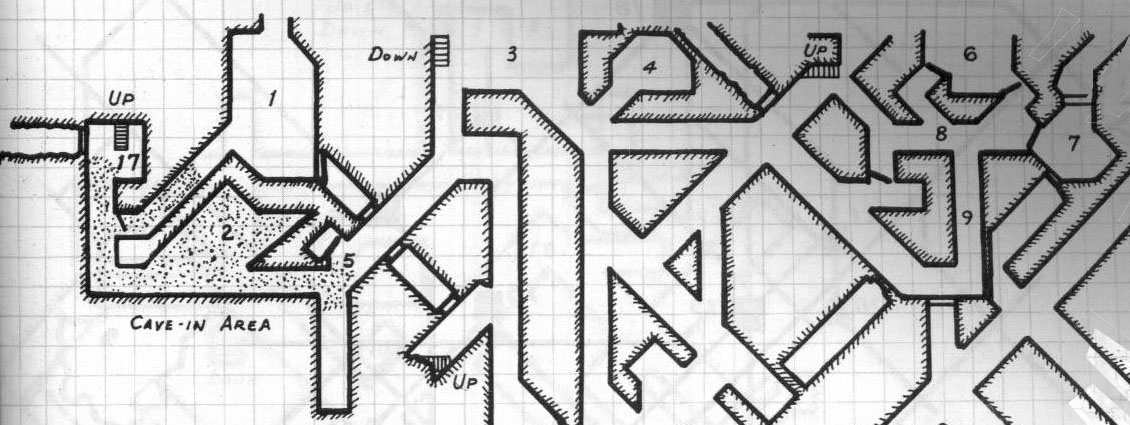

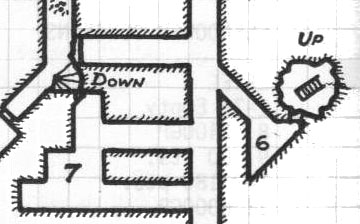

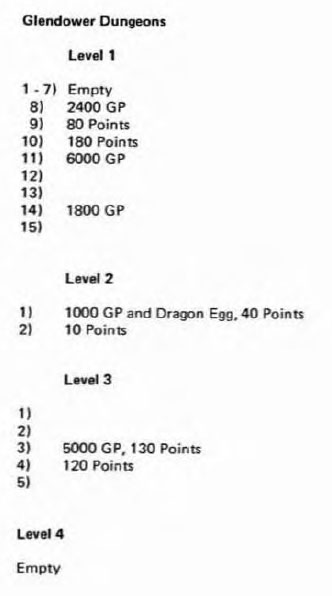

GLENDOWER TEMPLATE: I’m referring to this format as a Glendower template because it’s modeled after the presentation of the Glendower Dungeon in the First Fantasy Campaign:

As I described in Reactions OD&D: The Arnesonian Dungeon, I found this particular format fascinating because the combination of treasure + protection point budget creates a specific tactical “shape” for the dungeon, but allows the GM to completely reinvent the dungeon on-the-fly each time they run it: This time you spend the protection point budget on goblins and ogres and the Glendower Dungeons are an outpost of the Goblin King. Next time you spend them on Nazgul and it’s a wraith-infested ruin haunted by the ancient nobles who once ruled its halls. The next time it’s infested with giant spiders. And so forth.

A Glendower template can also allow the GM to more precisely indicate what the inhabited areas of “interest” are in a dungeon while still providing an ample opportunity for random generation to create spontaneity in actual play. (That is not the case here; this Glendower template of the Blackmoor dungeons was randomly generated.)

SEED 1: This was the result of me fully stocking the Blackmoor dungeon levels. This is the version of the dungeon that I’ve been running (and which it looks like I’ll be continuing to run for awhile longer as an open table).

SEED 2: To demonstrate the flexibility of the system, I started over and started a second seed of the entire dungeon. (This took about 45 minutes to do all seven levels.) Perhaps the most notable take-away, in my opinion, is how the same stocking procedure can create radically different versions of the same dungeon.

For example, in the Seed 1 version of the dungeon I generated only one encounter (featuring 23 hobbits) on Level 1 and Level 2 was also sparsely inhabited. In Seed 2, however, the upper level is filled with hostile fey (including an attack force in the very first room!) and Level 2 is crawling with bad guys. In play, entering the Seed 1 version of the dungeon was a slow, tense build as empty corridors rolled out behind the party. The Seed 2 dungeon, on the other hand, would be an immediate meatgrinder.

OBSERVATIONS FROM STOCKING

What have I learned from actually putting these stocking procedures into practice?

Primarily that the system starts breaking down for me around Level 5. There are two interlinked problems.

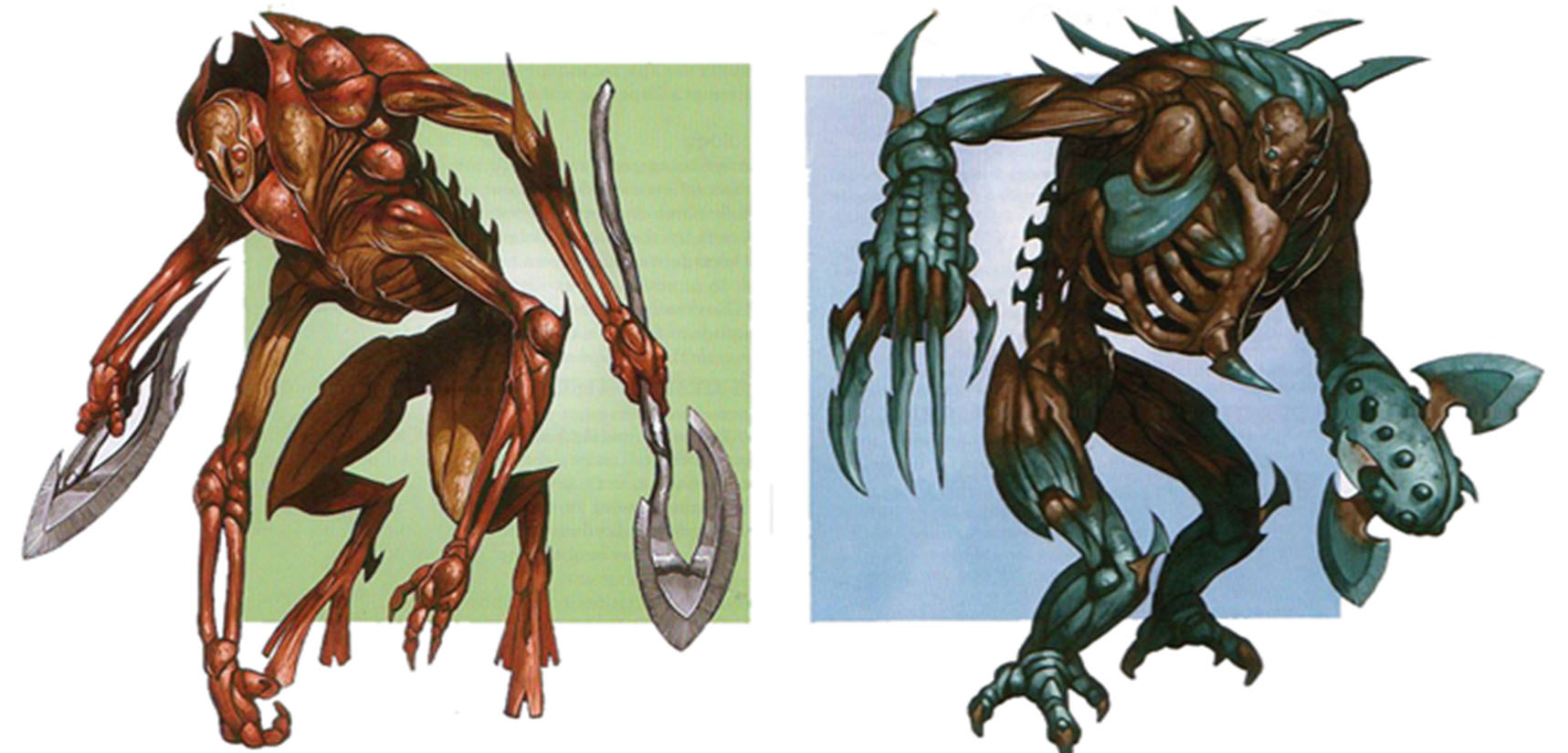

First, it feels weird for most of the Group III creatures to appear in small hordes. Getting results like 6 Balrogs or 5 Dragons feels weird. I’ve decided to roll with it and see how that develops in actual play, but one option to explore in the future would be tweaking the procedures to favor one “Big Boss” with minions generated from the Group I or Group II tables. However…

Second, regardless, the increased point values at the lower levels fund huge numbers of bad guys. Results like “50 Nazguls” or “Giant, Basilisk, 8 Nazguls, 11 Ogres” or “23 Ents” are quite common.

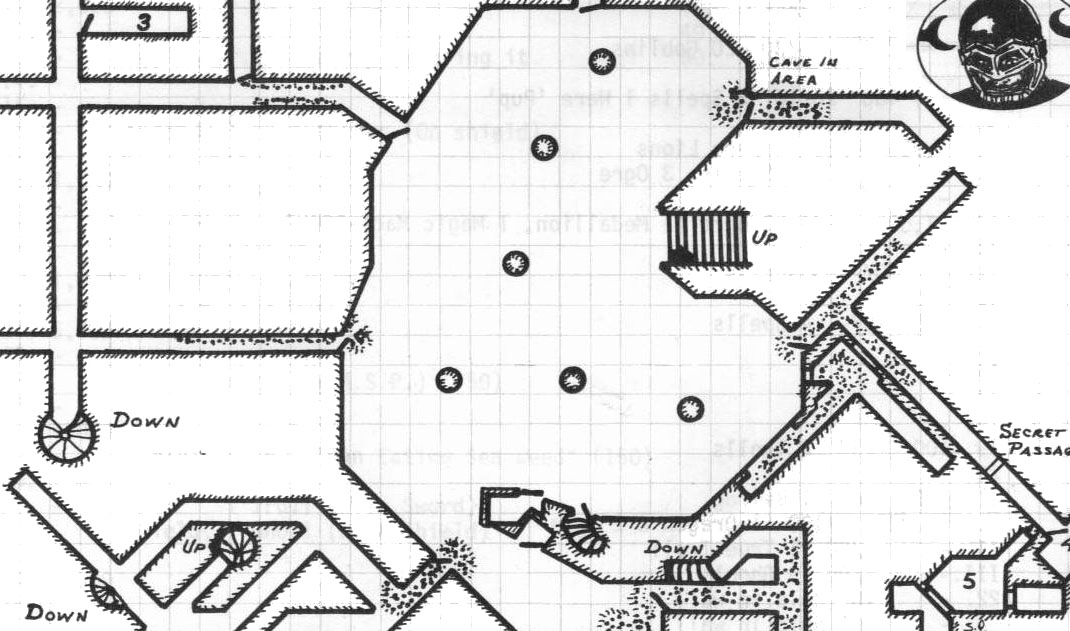

This is inherent to Arneson’s stocking method, but the maps of Castle Blackmoor don’t adjust to reflect the nature of the encounters being generated: The rooms on the lower levels remain tiny and cramped.

Based on Arneson’s surviving key of the lower levels, this doesn’t seem to have bothered him: For example, he keys 250 dwarves into a 10′ x 40′ long space. Or 60 ogres into a 10′ x 10′ room.

For the moment, I’ve decided to play it as it lies, simply letting the keyed results stand as they were generated. If my players manage to delve down to those lower levels, it’s possible that I will discover (or create) some method of play that makes sense of these sorts of encounters. Given my predilection for complex, multi-room tactical scenarios, for example, it probably wouldn’t be difficult to interpret large hordes in one room as actually spilling out into neighboring chambers. Another option would be to interpret such entries as actually suggesting that the keyed room is merely the entrance to some sub-level of the dungeon. You can find a suggestion of that in my Seed 1 notes:

Level 4, Area 13: 56 Elf/Fairy – crystal ball; they must live beyond a magic portal in this dead end

Perhaps I’ll grab a few random Dyson Logos maps and have them on hand and simply use them as necessary. To fit them into the tight geography of the Blackmoor dungeons may be a trifle difficult, but extradimensional portals and long inter-level passages that locate the sub-level somewhere else or drop down/up at steep angles to connect with the wider tunnel systems around Blackmoor can simplify the difficulties.

Upon reflection, I actually quite like this “outpost entrance” model: Use a handful of the indicated creatures as a “door guard” of sorts and then use the remaining creatures indicated to stock the sub-level / micro-dungeon behind the outpost entrance. In this model, the lower levels of the dungeon would fall naturally into armed enclaves linked to the central dungeon topography. (This also feeds well into my personal vision of the dungeon as a place where materiel both Ancient and Evil wells up from the depths. These outposts become literal wells from which strange and eldritch things emerge into the dungeon core.)

But I digress.

More generally, I would note that the problem here is not necessarily with the strength of the encounters generated, but rather with the fact that the maps weren’t drawn to reflect the results the stocking procedure was generating. If you were using these same procedures to stock your own dungeons, the problem can be trivially resolved by mapping accordingly.

USING MINIMALIST KEYS IN PLAY

Running a dungeon using a minimalist key is, of course, an act of improvisation: You take scraps of information, throw them into the cauldron of your imagination, and you see what comes spilling out. As you do this over time, the details you’re creating will begin interacting with each other and creating new details.

In some cases, a story will come spilling out of the key as you’re rolling it up. For example, look at Level 4 of Seed 1:

The dice got in a rut and filled the entire north side of this level with Fighting-Men. This section of the dungeon also features a number of connections to the wider network of tunnels which surrounds the Castle Blackmoor dungeons. These tunnels, in turn, feature a number of exits to the surface. Putting these facts together, it’s easy to “see” that these fighting-men are actually bandits, staging their raids out of this hideout.

Or look at Level 6 in Seed 2: Here the dice pumped out 70+ Nazgul. I don’t know exactly what those Nazgul are doing down there, but the entire level — let’s call it Wraith Hall — will be heavily influenced in terms of visuals and content by their domination here.

More ideas will come into focus once play begins. For example, as I mentioned before, on Level 1 of the dungeon I had only generated a single encounter featuring 23 hobbits in Area 6:

It became clear to me that this must mean that this entire corner of the first level must actually be a hobbit warren! If the PCs ever go over there, they’ll find round doors and curved tunnels that — if they’re human — are rather too small for comfort. What are the hobbits doing down here? Well, they were first met as the result of a random encounter roll, so I decided that they must be patrolling the upper levels of the dungeon for Baron Fant, keeping them clear of dangers. (Which is, of course, why the upper two levels are, in this version of the dungeon, relatively unpopulated.) Which is why the PCs met Sir Alcestis, a brave hobbit knight dressed in blue livery, and his crew of hobbit wardens.

Later the PCs find the secret doors leading to Area 9:

Checking my key I see that this area contains a magic sword (the N Sword), but not creatures. The odd shape of the rooms and the presence of the sword combine to create a creepy chamber with full-length mirrors on each of the three walls: Those looking into one of the mirrors will see themselves holding the sword in their hand.

What’s the sword look like? Well, I check the Sword Matrix and I see that the N Sword is an anti-lycanthropic blade. So I describe it as have a hilt of gray fur with a kind of “tassel” attached to it. (Why? No particular reason. It’s just the image that occurs to me.)

Finding the N Sword is particularly interesting in this specific context, however, because one of the PCs has been bitten by a lycanthrope earlier in the session. In rolling up its variable stats, I discover that it is only intelligent enough to communicate by “passing on gross emotions”, so when the PCs successfully extricate the sword from the puzzle of the three mirrors, I describe the “tassel” as curling up like the tail of an angry cat and pointing directly at the afflicted character. This ability to detect lycanthropes at a short range isn’t listed in the sword’s stat block, but it follows logically (and, more importantly, awesomely) from the creative chain we’ve been following to get to this point.

Next: Restocking the Dungeon