This 3rd Edition scenario was originally designed for my In the Shadow of the Spire campaign. I recently had cause to mention it while discussing the need to occasionally write-off the material you’ve prepped: Due to a series of odd events, the PCs in my campaign ended up falling in with a litorian named Wenra (who you’ll meet in detail below). At the end of one session they agreed to accompany him in exploring a dungeon complex he had recently discovered, but half of the party wasn’t firmly committed to the idea and at the beginning of the next session they managed to convince the others it wasn’t a good use of their time or resources. The rather lengthy adventure — which I had grown quite fond of — was laid aside.

The adventure itself is an adaptation of and radical expansion of two dungeons from the One Page Dungeon Contest: The Sunken Temple of Arnby Strange Stones and Escape from the Lost Laboratoriesby Wordman.

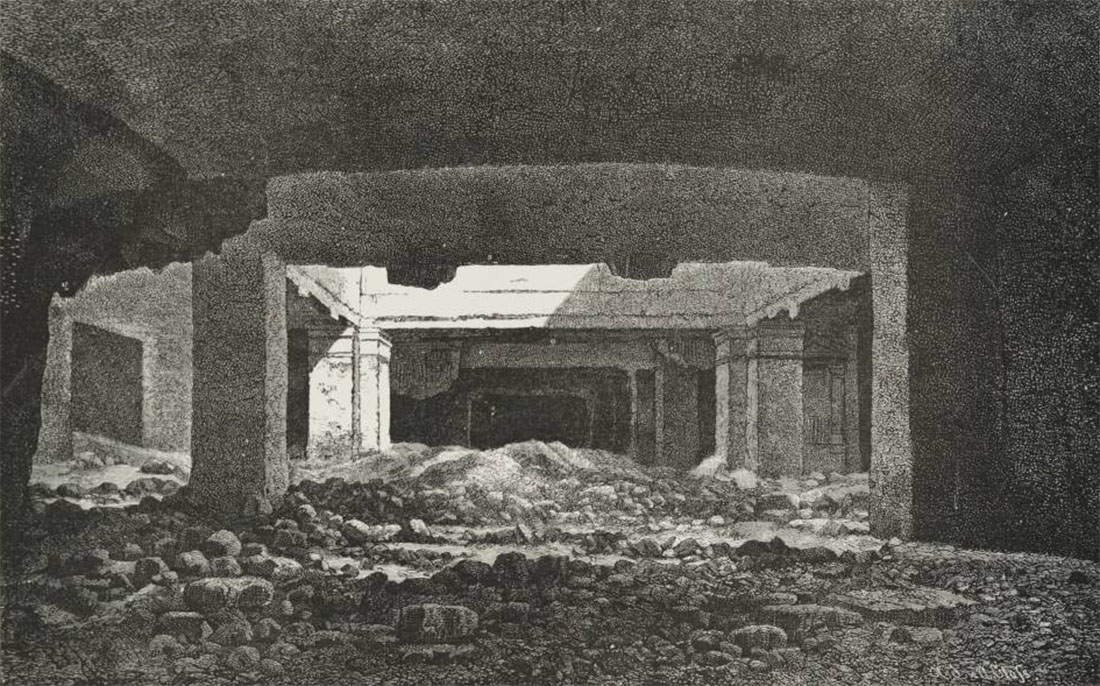

THE ARN

The Arn were a secret society during the era of the Sorcerer-Kings. (Much like the Brotherhood of the Silver Hand.) They constructed networks of underground laboratories to keep their work hidden and connected these laboratories using a teleportal network.

The Arn sect in the area around the City dabbled extensively into the chaotic magitech of the Banelord and Lithuin.

SORCEROUS BRAND OF ARN: These marked the members of the order. The branding irons can still be found in the Temple of Vehthyl (Laboratory 4).

BRONZE TABLETS OF ARN: Written in the secret arcane tongue of the Arn. Requires a read magic and comprehend languages spell, and still requires a 5/2 (failure starts over) Decipher Script check (DC 20, 1 hour per check). Each tablet generally has 1 spell on it.

THE WANDERER AND THE BEAR

Wenra is an Artathi — a member of the proud race of felinids who live on the southern continent. His animal companion is a bear named Seenmae.

Wenra recently discovered a secret door in the Catacombs beneath the City that open onto a long stairway leading down to the entrance of the Sunken Temple of Arn. Finding his way blocked by water, he returned to the surface to get a potion of waterbreathing (and ended up getting several doses of gillweed, see below) and to seek out adventurous companions to accompany him in exploring the ruins (which is where the PCs come in).

Wenra recently discovered a secret door in the Catacombs beneath the City that open onto a long stairway leading down to the entrance of the Sunken Temple of Arn. Finding his way blocked by water, he returned to the surface to get a potion of waterbreathing (and ended up getting several doses of gillweed, see below) and to seek out adventurous companions to accompany him in exploring the ruins (which is where the PCs come in).

Wenra believes that the sunken temple may lead to the Lost Laboratories of the Arn — elaborately concealed laboratories belonging to the arcane sect of Arn which were scattered around the City and only accessible through some sort of teleport network. (He is, in fact, right about this.)

Wenra has in his possession a red key which he believes will allow him to access the entire teleport network. Unfortunately, although it appears intact, it is actually broken. (Spellcraft DC 25 to identify the key; DC 35 to realize it’s not fully functional.)

GILLWEED: Chewing this heavily oxygenated weed allows a character to breathe underwater for up to 1 minute per dose.

WENRA

APPEARANCE: Broad-shouldered Artathi with golden fur. His mane has ribbons of blue-and-crimson threaded through it. His two front-fangs have scrollwork inking on them in the shape of a bear’s paws.

ROLEPLAYING:

- Hunched shoulders.

- Big laugh.

- Gleeful about delving (which often overrides caution).

BACKGROUND: Wenra was a member of one of the Artathi hunting bands that roam the rocky land north of the city. He left his tribe and came to the City to escape a wrath oath that was sworn against him by his brother (Tyrian) for sleeping with his wife (Bithbessa).

When he arrived in the City two years ago, Wenra became fascinated with the Catacombs beneath the city. He joined the Wanderer’s Guild and threw himself enthusiastically (if not always competently) into delving.

WENRA (CR 5) – Male Litorian – Ranger 7 – CG Medium Humanoid

DETECTION – low-light vision, Perception +10; Init +1; Languages Common, Goblin, Litorian

DEFENSES – AC 18 (+2 Dex, +1 Two-Weapon Defense, +5 +1 chain shirt of silent moves), touch 12, flat-footed 16; hp 61 (7d8+21)

ACTIONS – Spd 30 ft.; Melee +1 battleaxe +8/+8/+3/+3/+3 (1d8+5) or +1 battleaxe +12/+7 (1d8+5); Ranged +8; Base Atk +7/+2; Grapple +11; Atk Options favored enemy (animal) +4; Combat Feats Power Attack; Combat Gear caltrops, acid (x3), antitoxin (x2), holy water (x3), potion of cure light wounds

SQ animal companion, improved combat style (two-weapon), favored environment (underground), low-light vision, wild empathy, woodland stride

STR 18, DEX 15, CON 16, INT 13, WIS 10, CHA 12

FORT +8, REF +7, WILL +2

FEATS: Improved Animal Companion, Endurance*, Track*, Improved Two-Weapon Fighting*, Power Attack, Two-Weapon Defense, Two-Weapon Fighting* (* Bonus feat)

SKILLS: Climb +8, Handle Animal +11, Heal +5, Intimidate +3, Jump +8, Knowledge (dungeoneering) +9, Knowledge (geography) +3, Knowledge (nature) +7, Perception +12, Stealth +11, Search +12, Survival +4, Swim +7

POSSESSIONS: +1 chain shirt of silent moves, +1 battleaxe (x2), backpack (caltrops (x2), candle, chain, crowbar, grappling hook, hammer, pitons (x12), 50 ft. rope, torch (x12)), bandolier (acid x3, antitoxin x2, holy water x3, potion of cure light wounds), gillweed (12 doses)Endurance (Ex): +4 on Swim checks to avoid nonlethal damage; Constitution checks to avoid nonlethal damage from forced march/starvation/thirst, hold breath, nonlethal damage from cold and hot environments; Fort saves vs. suffocation damage. Can sleep in light or medium armor without becoming fatigued.

Favored Enemy (Ex): Gains +4 bonus on weapon damage, Bluff, Knowledge, Listen, Sense Motive, Spot, and Survival checks vs. Animals.

Favored Environment (Ex): Gains +4 bonus Hide, Listen, Move Silently, Spot, and Survival checks in Underground environments.

Wild Empathy (Ex): 1d20 + ranger level to improve animal’s reaction, resolve as Diplomacy.

Woodland Stride (Ex): Move through any non-magical undergrowth without speed penalty or damage.

Ranger Spells Prepared (CL 3)

1st (DC 12)—speak with animals

SEENMAE (CR 4) – N Large Animal

DETECTION – low-light vision, scent, Listen +4, Spot +7; Init +1

DEFENSES – AC 20 (-1 size, +1 Dex, +5 natural, +5 partial plate barding), touch 10, flat-footed 19; hp 72 (6d8+24)

ACTIONS – Spd 30 ft. (40 ft. w/o barding); Melee 2 claws +11 (1d8+8) and bite +6 (2d6+4); Ranged +4; Space 10 ft.; Reach 5 ft.; Base Atk +4; Grapple +16; SA improved grab; Combat Feats Run

SQ familiar abilities (link, share spells), low-light vision, scent

STR 27, DEX 13, CON 19, INT 2, WIS 12, CHA 6

FEATS: Endurance, Run, Track

SKILLS: Listen +4, Spot +7, Swim +8* (+12 w/o barding)

POSSESSIONS: partial plate bardingImproved Grab (Ex): Start grapple as free action off claw attack, no attack of opportunity.

*Skills: +4 racial bonus on Swim checks.

WENRA’S PATH

Wenra’s Path leads:

- Through the Catacombs to a door.

- Down a long stairway (with

- The stairway continues down into sunken passages.

- The sunken passages lead to Area 1 of the Sunken Temple of Arn.

Go to Part 2: The Sunken Temple of Arn

Any material in this post not indicated as Product Identity in the Open Gaming License is released by Creative Common Attribution-Share Alike 3.0.

And one of the great strengths of Yes, but… is that it’s actually quite difficult to game the system:

And one of the great strengths of Yes, but… is that it’s actually quite difficult to game the system: