Yesterday I talked about the ability to control the pace of encounters in D&D, and how that control can tip the balance of power between the fighters and the wizards. A lot of people believe that you need to completely rip apart the system in order to correct this imbalance, but in my experience — once you understand the true source of the problem — you can actually get a lot of mileage out of a handful of meaningful tweaks.

For example, one of the most powerful pace-control combinations at higher levels of play is the scrying-and-teleport combo (also known as a “scry and die”): You use scrying to find your target, teleport to reach them, blast the crap out of them before they have a chance to prepare or defend themselves, and then teleport away again.

I’ve seen DMs simply remove teleport and scrying from the game entirely, but I’ve found that a gentler approach works just as well (without removing some nifty abilities entirely from the game).

TELEPORT HOUSE RULES

These rules apply to any spells of the Conjuration (Teleportation) type and similar effects.

- You can only teleport a number of miles equal to your caster level. (When teleporting through the use of a racial ability, the distance is limited to a number of miles equal to your total HD.)

- Teleporting characters or objects disappear instantly, but teleportation takes a number of rounds equal to the number of miles traveled (minimum of 1 round). During this time, characters at the destination of the teleport can make a Spot check (DC 20). If the check succeeds, they are aware of the incoming teleport. If the distance of the teleport is a mile or less, characters at the receiving end of the teleport will only have a surprise round in which to take actions before the teleport is completed.

- Teleport Trace: Outgoing teleport spells leave a teleport trace during the duration of the teleport. Characters at the source of a teleport can make a Spot check (DC 20) to spot the teleport trace. Teleport spells and similar effects can be used to automatically follow the original teleport, although the caster will not know where the teleport spell goes until they arrive. Scrying sensors can be sent through a teleport trace.

- Dispelling Teleports: Spellcasters who are aware of the incoming teleport can attempt to counterspell the teleport (even though they are unable to see the caster).

- Blocked Teleports: If a teleport is counterspelled, blocked, or otherwise disrupted the character or object being teleported returns to its original location.

- Gate: The gate spell can be used to circumvent the distance limitation on teleportation. The casting time for the spell is equal to 1 round per mile traveled or 1d10 minutes for interplanar travel. During the casting time, the gate is clearly visible from both ends and events at the other end of the gate can be seen murkily through it (Spot checks suffer a -10 penalty). Once the gate is established, travel through the gate is instantaneous.

DESIGN NOTES

The distance limitation was actually added to my house rules for flavor reasons and can be ignored if you’re just interested in tweaking the rules for balance purposes. (The original group of PCs in my current campaign world wanted a campaign featuring a Lord of the Rings-style cross-country epic. Long-range teleportation would have undermined that goal: Lord of the Rings is a very different story when Gandalf just teleports the Fellowship from Rivendell to Mt. Doom. Long-range teleportation is also one of those abilities which, if you considered its practical impact on the world, would completely transform society.)

The meaningful tweaks here is adding a duration to the teleport itself and allowing characters at the destination or source of the teleport to spot the teleport and interact with it in meaningful ways. The ability to use a teleport spell to facilitate hit-and-run tactics isn’t removed from the game, but it is given its own unique effects and consequences. The target of the technique, for example, can simply choose to run away. Or prep their defenses. Or call for help. The PCs could actually end jumping into the middle of a massive ambush of their own making.

Similarly, PCs can’t count on teleport necessarily being an automatic escape plan after the hit-and-run has been completed: Enemy spellcasters can follow them through their teleports.

It’s a small adjustment, but it means that “scry and die” is no longer clearly superior option to a traditional assault: It has its own strengths and weaknesses, which will sometimes make it better than a traditional assault and sometimes worse.

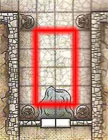

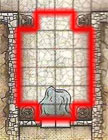

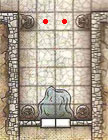

In this section of the encounter, there are four cherub statues. When triggered, the cherubs create an arcane cage to trap a victim. The cherubs then pour water into the arcane cage, which triggers a whirlpool effect that smashes the victim into the cherub statues and cause them to take damage.

In this section of the encounter, there are four cherub statues. When triggered, the cherubs create an arcane cage to trap a victim. The cherubs then pour water into the arcane cage, which triggers a whirlpool effect that smashes the victim into the cherub statues and cause them to take damage.