I’ve been on a pulp fantasy kick for the past month or so: I started with Robert E. Howard, having finally secured (by way of the Science Fiction Book Club) a hardcover copy of what promises to be the first true edition of his Conan stories to be issued in the States. From that familiar territory I spun off for a quick foray through Henry Kuttner’s imaginative Prince Raynor stories before returning to Howard for the outstanding – if unfortunately few – Cormac Mac Art stories. I then took a voyage of peril and pleasure across Clark Ashton Smith’s forgotten continent of Zothique before turning my attention to Fritz Leiber’s legendary duo: Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser.

I’ve been on a pulp fantasy kick for the past month or so: I started with Robert E. Howard, having finally secured (by way of the Science Fiction Book Club) a hardcover copy of what promises to be the first true edition of his Conan stories to be issued in the States. From that familiar territory I spun off for a quick foray through Henry Kuttner’s imaginative Prince Raynor stories before returning to Howard for the outstanding – if unfortunately few – Cormac Mac Art stories. I then took a voyage of peril and pleasure across Clark Ashton Smith’s forgotten continent of Zothique before turning my attention to Fritz Leiber’s legendary duo: Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser.

From there I had intended to set sail for the lands of either Moorcock’s Elric or Wagner’s Kane, but – in truth – I find myself so disheartened that I am instead turning my attention to wholly different pastures for awhile.

But I fear that I set my premise before my scene. Let me back up for a moment.

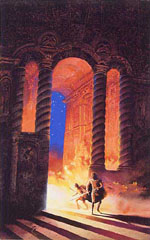

For those who don’t know, Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser are famed heroes of the sword and sorcery genre. First unleashed in the pages of the pulps, their literary career spanned almost five decades, coming to an end only with Leiber’s death in the early ‘90s. Their tales are most commonly available in seven authoritative collections: Swords and Deviltry, Swords Against Death, Swords in the Mist, Swords Against Wizardry, Swords of Lankhmar, Swords and Ice Magic, and The Knight and Knave of Swords.

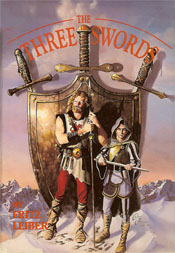

I first read their adventures in junior high, savoring the two omnibuses which collected the first six of these volumes: The Three Swords and Swords’ Masters. Coming back to them now, nearly fifteen years later, I had only dim and disjointed memories of the two dashing swashbucklers, their gritty city of Lankhmar , and the mystic-laden land of Nehwon .

On this return trip, I found myself harboring a great deal of uneven disappointment. In short, I found that the stories of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser could be roughly divided into two camps – the outstanding and the painfully mediocre – with the latter far outnumbering the former.

Nor can one simply say, as one can in so many cases, that the earlier tales are superior to the hack work of the later. “Ill Met in Lankhmar”, The Swords of Lankhmar, and even the somewhat mixed “Rime Isle”, although among the later works, would make the list of those stories I would recommend. Although, that being said, I think it is clear that, as the series continued, a certain dreary repetition and self-conscious cleverness began to consistently diminish the stories.

Perhaps the best way to approach this inconsistent and self-crippling series is through a volume-by-volume summary of impressions.

SWORDS AND DEVILTRY: Fortunately, the most consistent volume in the series is also the first, although it contains only three tales. “The Snow Women” and “The Unholy Grail” each tell a tale of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser before their fateful and legendary meeting in Lankhmar. The former is a top-notch tale of youth and magic in the frozen north, keenly demonstrating the fantastic and unique vision which Leiber is capable of delivering. The latter, although strongly crafted, is a somewhat weaker tale – its plot more commonplace in its conception. The volume is rounded out by “Ill Met in Lankhmar”, which is the tale of the first true meeting of our destined heroes. It is also a powerfully tragic story, and its strength is best described by the fact that it represented my strongest memory of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser before returning to the series.

SWORDS AND DEVILTRY: Fortunately, the most consistent volume in the series is also the first, although it contains only three tales. “The Snow Women” and “The Unholy Grail” each tell a tale of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser before their fateful and legendary meeting in Lankhmar. The former is a top-notch tale of youth and magic in the frozen north, keenly demonstrating the fantastic and unique vision which Leiber is capable of delivering. The latter, although strongly crafted, is a somewhat weaker tale – its plot more commonplace in its conception. The volume is rounded out by “Ill Met in Lankhmar”, which is the tale of the first true meeting of our destined heroes. It is also a powerfully tragic story, and its strength is best described by the fact that it represented my strongest memory of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser before returning to the series.

SWORDS AGAINST DEATH: The second volume in the series begins to show the inconsistency I’m talking about, particularly in the short bridging stories which I believe Leiber wrote specifically for these collections. “The Jewels in the Forest ” and “Thieves’ House”, two of the oldest stories, are the highlights here, and come highly recommended. Running close behind are “The Howling Tower” and “Claws of the Night” – the former being slight, but imaginative; while the latter comes as close to being a prototypical tale of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser as you are likely to find (mixing thievery, gods, and sly humor across the backdrop of Lankhmar).

SWORDS AGAINST DEATH: The second volume in the series begins to show the inconsistency I’m talking about, particularly in the short bridging stories which I believe Leiber wrote specifically for these collections. “The Jewels in the Forest ” and “Thieves’ House”, two of the oldest stories, are the highlights here, and come highly recommended. Running close behind are “The Howling Tower” and “Claws of the Night” – the former being slight, but imaginative; while the latter comes as close to being a prototypical tale of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser as you are likely to find (mixing thievery, gods, and sly humor across the backdrop of Lankhmar).

Much of this volume, however, is thoroughly pedestrian. To this category belong “The Bleak Shore”, “The Sunken Land”, “The Seven Black Priests”, and “Bazaar of the Bizarre”. (Although, in their favor, I will note that these all have their moments of fantastic vision. The last, however, is a very thin pastiche.) Finally, it would be charitable to describe the last two tales offered here – “The Circle Curse” and “The Price of Pain-Ease” – as thoroughly mediocre. It would be more accurate to simply describe them as bad.

SWORDS IN THE MIST: The third volume is even more uneven than the second. On the one hand, it arguably contains the two best stories in the series: The first of these, “Lean Times in Lankhmar”, is a masterfully crafted tale. Its characters keep you enthralled while its fanciful premise is cleverly worked into an utterly hilarious conclusion. It reminds me strongly of Terry Pratchett at his finest. (Pratchett’s Small Gods, in particular, owes an obvious debt to this story.) The second gem to be found here is “Adept’s Gambit”, which is also the first tale of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser written by Leiber. Set in a mythically tinged epoch of ancient history, the tale is faintly resonant with the finest creations of Lovecraft, Howard, and Clark Ashton Smith, but possesses a flair and unique sense of character which makes it all Leiber’s own.

SWORDS IN THE MIST: The third volume is even more uneven than the second. On the one hand, it arguably contains the two best stories in the series: The first of these, “Lean Times in Lankhmar”, is a masterfully crafted tale. Its characters keep you enthralled while its fanciful premise is cleverly worked into an utterly hilarious conclusion. It reminds me strongly of Terry Pratchett at his finest. (Pratchett’s Small Gods, in particular, owes an obvious debt to this story.) The second gem to be found here is “Adept’s Gambit”, which is also the first tale of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser written by Leiber. Set in a mythically tinged epoch of ancient history, the tale is faintly resonant with the finest creations of Lovecraft, Howard, and Clark Ashton Smith, but possesses a flair and unique sense of character which makes it all Leiber’s own.

Unfortunately the rest of this volume can’t compare with these two classics: “The Cloud of Hate” and “When the Sea-King’s Away” are forgettable clichés, while “Their Mistress, the Sea” and “The Wrong Branch” are ham-fisted, half-baked afterthoughts attempting to create an unnecessary bridge between one tale and the next.

SWORDS AGAINST WIZARDRY: The bulk of this volume is taken up by two lengthy tales, “Stardock” and “The Lords of Quarmall”. Both stories play out across a fantastic and vividly imagined landscape populated with strange cultures and larger-than-life characters. These two tales give Swords Against Wizardry perhaps the strongest base of any volume in the series. Unfortunately, the collection is also padded out with a couple of bridging stories – “The Witch’s Tent” and “The Two Best Thieves of Lankhmar” – which have a bit more substance to them than the other bridging stories, but are still mediocre offerings at best.

SWORDS AGAINST WIZARDRY: The bulk of this volume is taken up by two lengthy tales, “Stardock” and “The Lords of Quarmall”. Both stories play out across a fantastic and vividly imagined landscape populated with strange cultures and larger-than-life characters. These two tales give Swords Against Wizardry perhaps the strongest base of any volume in the series. Unfortunately, the collection is also padded out with a couple of bridging stories – “The Witch’s Tent” and “The Two Best Thieves of Lankhmar” – which have a bit more substance to them than the other bridging stories, but are still mediocre offerings at best.

THE SWORDS OF LANKHMAR: This is, in fact, the only stand-alone novel in the series. It tells the sprawling saga of an attempted invasion (of a most unusual size and character) aimed against the great city of Lankhmar . Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, of course, almost single-handedly turn back this invasion – although the path they take is anything but simple or straight-forward.

THE SWORDS OF LANKHMAR: This is, in fact, the only stand-alone novel in the series. It tells the sprawling saga of an attempted invasion (of a most unusual size and character) aimed against the great city of Lankhmar . Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, of course, almost single-handedly turn back this invasion – although the path they take is anything but simple or straight-forward.

The Swords of Lankhmar is not the best story told of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, but it is perhaps the greatest. The expanded format allows Leiber a chance to stretch his muscles, and he accepts the challenge admirably by weaving a tapestry not only expansive in its imaginings but detailed in its fancies.

Perhaps the most intriguing thing to me about this novel is the clear inheritance its narrative receives from fairy tales. Whereas most writers of sword-and-sorcery trace their antecedents back to classical myth and legend, Leiber’s heroes clearly inhabit a world inspired as much as by Hans Christian Anderson as it is by Beowulf. And it is perhaps this, more than anything else, which gives these stories a unique distinction in the field.

SWORDS AND ICE MAGIC: Unfortunately, after The Swords of Lankhmar the series appears to have spent its creativity. Swords and Ice Magic, the sixth volume, is largely an unimaginative regurgitation of the themes, plots, and characters found earlier in the series. The first five stories in this collection (“The Bait”, “Beauty and the Beasts”, “Trapped in Shadowland”, “The Bait”, and “Under the Thumbs of the Gods”) are simply dreadful wastes of time. In fact, they are all essentially the same story: Distant powers or gods attempt to kill Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, who – for their part – accept the improbable with stoic complacency while thoroughly and effortlessly thwarting the attempts each time. Unfortunately, this is also a story which was told twice before in these collections.

SWORDS AND ICE MAGIC: Unfortunately, after The Swords of Lankhmar the series appears to have spent its creativity. Swords and Ice Magic, the sixth volume, is largely an unimaginative regurgitation of the themes, plots, and characters found earlier in the series. The first five stories in this collection (“The Bait”, “Beauty and the Beasts”, “Trapped in Shadowland”, “The Bait”, and “Under the Thumbs of the Gods”) are simply dreadful wastes of time. In fact, they are all essentially the same story: Distant powers or gods attempt to kill Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, who – for their part – accept the improbable with stoic complacency while thoroughly and effortlessly thwarting the attempts each time. Unfortunately, this is also a story which was told twice before in these collections.

Fortunately, things then take a slight turn for the better. The sixth story, “Trapped in the Sea of Stars ”, is badly contrived and nearly plotless, but makes up for it through the vivid description of its sense-of-wonder sea voyage. There is, in fact, no particular story here at all – but the visions conjured forth by Leiber’s prose are worth the price of admission.

The last two stories in the collection – “The Frost Monstreme” and “Rime Isle” – are, in fact, two halves of a single story. Although still flawed by an increasingly rambling style, self-conscious commentary, and regurgitation of plot and imagery, this story still has a lot to offer: Clever interactions of character, epic sensibility, charming wit, and wondrous feats are offered up with a melancholic flair.

THE KNIGHT AND KNAVE OF SWORDS: Sadly, however, that is the end of it. This last collection of stories offers nothing but an imagination apparently spent. “Sea Magic”, “The Mer She”, and “The Curse of the Smalls and the Stars” each offer us regurgitated plots while doing nothing more than shuffling around the characters and magic items presented in “Rime Isle” to little sense of purpose or accomplishment.

THE KNIGHT AND KNAVE OF SWORDS: Sadly, however, that is the end of it. This last collection of stories offers nothing but an imagination apparently spent. “Sea Magic”, “The Mer She”, and “The Curse of the Smalls and the Stars” each offer us regurgitated plots while doing nothing more than shuffling around the characters and magic items presented in “Rime Isle” to little sense of purpose or accomplishment.

Finally, in “The Mouser Goes Below”, Leiber pulls the same trick: Shuffling around characters and devices already well-worn beyond any effective use. The only difference to be found is that Leiber pulls his reused material from a larger portion of the series, rather than a single story.

I also found another trend in this last volume particularly disconcerting: A pointless coarseness which was previously absent from the series. I’m not sure what Leiber was attempting to accomplish by suddenly inundating the narrative with “long poniards” piercing “cunts and arse holes”, but the effect was merely distasteful.

In the end, I think this was a series which long-outlived its creator’s interest. Or, at the very least, his ability. The later offerings become increasingly repetitive and unimaginative, as if Leiber had simply run out of new ideas to share. Unfortunately, in collected form, these lackluster efforts seem to out-mass and actively detract from those stories which legitimately earn Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser a place of high honor in the pantheon of fantasy heroes.

Indeed, I found myself unable to finish the series. Swords and Ice Magic had seriously fatigued my interest, and I pushed on with The Knight and Knave of Swords only because (a) I had never read that final volume and (b) I wanted to finish what I had started.

But, in the end, I could manage no further than the mid-point of “The Mouser Goes Below”. Leiber pinioned the Mouser – immobile, invisible, and speechless – in order to have him bear witness to a gratuitously graphic description of one of his former loves having her maid stripped bare, fondled in the cunt and arse hole, and then given instruction on “naked serving”. After several pages of this pointlessly turgid prose I finally gave up and closed the book.

If I ever return to the adventures of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, it shall be a markedly proscribed path I take through their tales. Such a journey would look something like this:

“The Snow Woman”

“The Unholy Grail”

“Ill Met in Lankhmar”

“The Jewels in the Forest”

“Thieves’ House”

“The Bleak Shore”

“The Howling Tower”

“The Sunken Land”

“The Seven Black Priests”

“Claws of the Night”

“Lean Times in Lankhmar”

“When the Sea-King’s Away”

Adept’s Gambit

“Stardock”

“The Lords of Quarmall”

The Swords of Lankhmar

“The Frost Monstreme”

“Rime Isle”

I suspect this is less than half of the words written by Leiber of the two greatest swordsmen to ever live in this or any other universe, but it is decidedly the better half. And it, unlike the balance of the series, comes with my highest recommendation.

GRADES:

GRADES:

SWORDS AND DEVILTRY: A-

SWORDS AGAINST DEATH: B+

SWORDS IN THE MIST: A-

SWORDS AGAINST WIZARDRY: A-

SWORDS IN LANKHMAR: A-

SWORDS AND ICE MAGIC: B

KNIGHT AND KNAVE OF SWORDS: D

Fritz Leiber

Published: 1940-1990

Publisher: Various

Buy Now!

The FDA needs to add Bujold novels to its list of controlled substances. They’re too damn addictive.

The FDA needs to add Bujold novels to its list of controlled substances. They’re too damn addictive. (2) The detailed, believable, and moving portrayals of her characters. Bujold is one of those authors seemingly incapable of producing cardboard characters. Even the bit parts who show up for no more than a page or so are given a unique identity, personality, and presence. And her main characters are drawn with a depth and humanity which make them either beloved or hated without ever hitting a false note.

(2) The detailed, believable, and moving portrayals of her characters. Bujold is one of those authors seemingly incapable of producing cardboard characters. Even the bit parts who show up for no more than a page or so are given a unique identity, personality, and presence. And her main characters are drawn with a depth and humanity which make them either beloved or hated without ever hitting a false note.