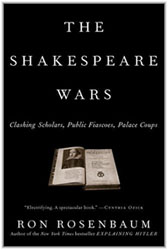

I’ve recently been reading The Shakespeare Wars by Ron Rosenbaum and writing a few essays in an effort to dissect some of the irrational examples of scholastic exuberance he highlights in the book. This essay, however, changes the focus to Rosenbaum himself.

I’ve recently been reading The Shakespeare Wars by Ron Rosenbaum and writing a few essays in an effort to dissect some of the irrational examples of scholastic exuberance he highlights in the book. This essay, however, changes the focus to Rosenbaum himself.

The topic: Shylock.

Rosenbaum’s position:

It’s the most truthful and the most terrible Shylock I’ve seen. Truthful, in part, because it’s a throwback to the original, a throwback to the deeply repellent character Shakespeare created. A throwback that has no truck with contemporary cant of the sort that attempts to exculpate Shakespeare and Shylock, evade or explain away the anti-Semitism. It doesn’t fall victim to the intellectual fallacy, the comforting but deluded evasion that has pervaded many recent productions of The Merchant of Venice: the belief that if you make Shylock a nicer guy, play him with more dignity, play up the cruelty of the Christians as well, you can somehow transcend the ineradicable anti-Semitism of the caricature.

The problem with the warm and fuzzy Shylock, the feel-good Shylock you might say, is that it doesn’t diminish, it actually exacerbates, deepens the anti-Semitism of the play as a whole. The more “nice” you make the moneylender, the more you end up making the play not about the villainy of one Jew, but the villainy of all Jews, a deep-seated villainy that subsists beneath the surface even in those who appear “nice” on the surface. The more warm and fuzzy you make Shylock, the more you make it a play about the fact that even such a Jew will not hesitate, when it comes down to it, to take a knife and cut the heart out of a Christian.

The central contention of Rosenbaum’s argument is that Shylock’s final act (when he attempts to commit an act of legalized murder) is a piece of unforgivable villainy that confirms the bigotry of the anti-Semitic. Thus, the nicer you make Shylock, the worse the message becomes: No matter how nice a Jew may seem, the truth is that all Jews are murdering monsters.

THE PROBLEM

But for Rosenbaum’s thesis to stick, he has to overcome a rather sizable hurdle. In The Merchant of Venice, Shylock says:

Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions; fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, heal’d by the same means, warm’d and cool’d by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that. If a Jew wrong a Christian, what is his humility? Revenge. If a Christian wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by Christian example? Why, revenge. The villainy you teach me, I will execute, and it shall go hard but I will better the instruction.

If you prick us, do we not bleed? This is one of the most beautiful and heart-rending evocations of the basic humanity which transcends all bigotries. And if The Merchant of Venice is, in fact, as viciously anti-Semitic as Rosenbaum claims, then it seems painfully out of place.

In short, the only way to accept an anti-Semitic reading of The Merchant of Venice is if you can explain away what may be the most eloquent skewering of anti-Semitism ever written. Rosenbaum, seeing the problem, writes:

But what about Shylock’s famous speech in his defense: “Hath not a Jew eyes? … If you prick us, do we not bleed?” one is inevitably asked. Some might argue that this indicated that Shakespeare had a more advanced consciousness than the medieval anti-Semitism that persisted into his time. Perhaps. But if the speech is read to its bitter end “do we not bleed” bleeds any poignancy dry as it turns out to be a rationale for vengefulness: If we are alike in these respects, “If you wrong us shall we [just as you] not revenge?” as well.

There are two problems with Rosenbaum’s argument.

First, he doesn’t actually explain why we should ignore the speech. He seems to be relying on an unspoken premise that “revenge is evil”. But even if we accept the premise, Rosenbaum’s conclusion doesn’t follow.

Second, Rosenbaum is setting up a false dichotomy. He’s saying “if Shylock is a villain, then the play is anti-Semitic”. Then he concludes that Shylock is a villain, ergo the play is anti-Semitic. But in setting up this dichotomy, Rosenbaum may be missing the entire point of the play.

THE POINT

When we first see Shylock and Antonio on the stage together, Shylock says:

Signior Antonio, many a time and oft

In the Rialto you have rated me

About my monies and my usances:

Still have I borne it with a patient shrug,

(For sufferance is the badge of all our Tribe.)

You call me misbeliever, cut-throated dog,

And spat upon my Jewish gaberdine,

And all for use of that which is mine own.

Well then, it now appears you need my help:

Go to then, you come to me, and you say,

“Shylock, we would have monies.” You say so;

You that did void your rheum upon my beard,

And foot me as you spurn a stranger cur

Over your threshold. Monies is your suit.

What should I say to you? Should I not say,

“Hath a dog money? Is it possible

A cur should lend three thousand ducats? Or

shall I bend low, and in a bond-mans key

With bated breath, and whispering humbleness,

Say this: “Fair sir, you spat on me on Wednesday last;

You spurn’d me such a day; another time

You call’d me dog: and for these courtesies

I’ll lend you thus much monies.”

This speech, I think, sets up the core dynamic of the play: Hatred begets hatred.

It’s not that Shylock is pretending to be a nice guy while secretly being a Jewish monster. It’s that the Christians treating him like a monster is what turns him into a monster.

Elsewhere in his book, Rosenbaum quotes a speech from the “Hand D” of Sir Thomas More that many believe may be written by Shakespeare. In reading it, I was struck by a similar theme. Thomas More is confronting a riotous, anti-immigrant crowd. As Rosenbaum writes, “the sympathy is with the immigrant-bashing nativist poor”, but then Hand D takes over. Sir Thomas More stands up before the crowd and says:

Grant them removed and grant them this your noise

Hath chid down all the majesty of England,

Imagine that you see the wretched strangers,

Their babies at their backs, with their poor luggage

Plodding to th’ ports and coasts for transportation,

And that you sit as kings in your desires,

Authority quite silenc’d by your brawl,

And you in ruff of your opinions cloth’d,

What had you got? I’ll tell you: you had taught

How insolence and strong hand should prevail,

How order should be quell’d and by this pattern

Not one of you should live an aged man,

For other ruffians, as their fancies wrought,

With self-same hand, self reasons, and self right,

Would shark on you, and men like ravenous fishes

Would feed on one another.

Again, we see this theme of hatred creating hatred; intolerance breeding intolerance.

In the end I think this is not only a more legitimate interpretation of The Merchant of Venice, I think it’s also a more interesting one.

Rosenbaum presents his opinion of Shylock within the context of a larger thesis that Shakespeare’s villains don’t need any explanation or motivation — they’re just evil. I think this is, in general, an overly-simplistic, one-size-fits-all explication of the Bard. And I think it specifically causes Rosenbaum to overlook the complexity of The Merchant of Venice.

ROSENBAUM’S DEFENSE

But if Ron Rosenbaum were reading this essay, I know what his response would be, because he trots it out a half dozen times or more in The Shakespeare Wars:

Sorry, it’s just not a character you can make nice about, or rationalize as some do, by emphasizing the play’s critique of the cruel mockery of the money-hungry Christians as well. Christians weren’t slaughtered for their religious stereotypes in Europe; Jews were. None of the Christian characters played the ugly and vicious role Shylock did in Nazi propaganda. When one encounters this allegedly sophisticated Shakespeare-made-the-Christians-worse evasion, one has to ask why the Nazis put on fifty productions of Merchant. Because of its critique of the Christians?

Basically, this becomes Rosenbaum’s first and last line of defense: If you claim that there’s a sympathetic reading of Shylock to be had, then you’re a Nazi. (Or, at best, a Nazi-sympathizer.)

One could delve into the problems with Rosenbaum’s defense. (For example, just because Shylock can be played as a racist caricature, it doesn’t follow that he should be. Or perhaps the fact that the German productions would have been translated, offering plentiful opportunities to strip out Shakespeare’s theme and replace it with something uglier.) But it’s pointless, because there is no actual substance behind Rosenbaum’s repeated insistence that “if the Nazis performed it, it must be evil”. If he pulled this online, he would be rightfully called out for Godwinizing the discussion.

(And it was, in fact, this particular bit of intellectual dishonesty that prompted me to start writing this response.)

HEDGING MY BETS

With that being said, I have never performed a deep study of The Merchant of Venice. And even my casual readings and viewings have made it abundantly clear that there are no easy answers when it comes to the text. For example, before offering any other rationale, Shylock says, “I hate him for he is a Christian.” And there remains the open question of exactly how the behavior of the Christians in the play would have been interpreted by an Elizabethan audience: We see their behavior as abhorrent and are thus inclined to interpret them as negative portrayals. But if you don’t view their behavior as abhorrent, does that remain true? Is the play condemning them or are we condemning them?

But whatever complexities the text may offer, it remains absolutely true that it explicitly says both that, “Shylock does what he does because Antonio did what he did.” and “There is no difference between a Jew and a Christian.”

Any responsible reading of the text must take those elements of the text into account. It cannot, as Rosenbaum does, simply ignore them.