The Red Company of Goldsmiths is maintained as a small subsidiary of the Goldsmiths’ Guild (which, in turn, is largely controlled by the Ironworkers’ Guild). The Vladaams maintain it primarily to launder stolen funds and goods from their other enterprises.

Gold Strips: Suitable for crafting. Each strip is marked with the “V” sigil of the Vladaams (making them easily traceable).

| DENIZENS - DAY | Location |

|---|---|

| 2 Vladaam Advanced Guards | Entrance |

| 2 Vladaam Advanced Guards | Area 1 |

| Goldsmiths (2d4+2) | Area 1 |

| Telidor | Area 4 (60% chance) |

| DENIZENS - NIGHT | Location |

| 2 Vladaam Advanced Guards | Entrance |

| 4 Vladaam Advanced Guards + 2 Vladaam Mages | Area 2 |

| Telidor | Area 4 (10% chance) |

Goldsmiths: Use artisan stats, Ptolus, p. 606.

- Proficiency (+2): Jeweler’s Tools

- Equipment: 1d10 x 1d10 gp, jeweler’s tools, Vladaam deot ring

Guildsman District

Gold Street – E9

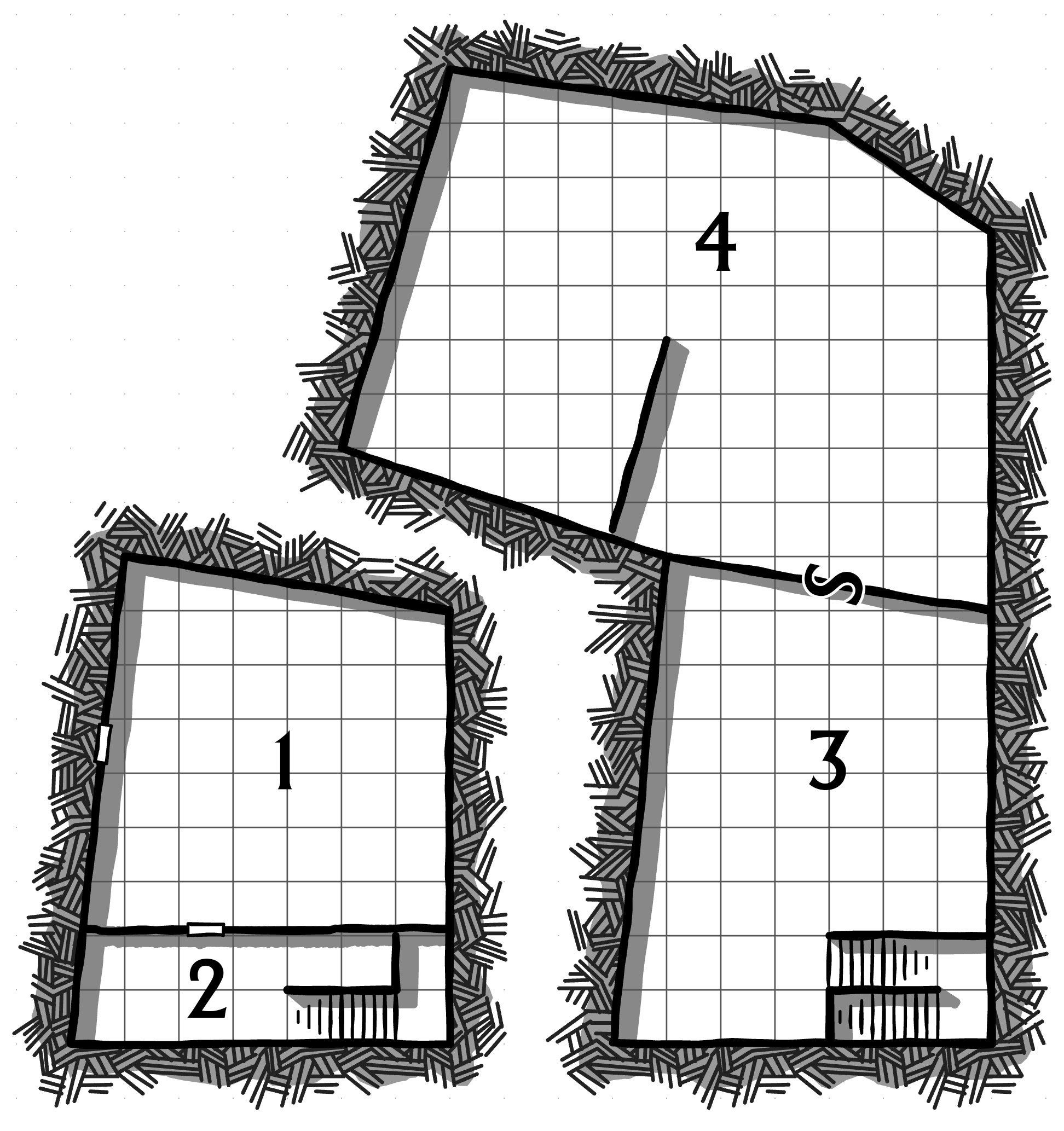

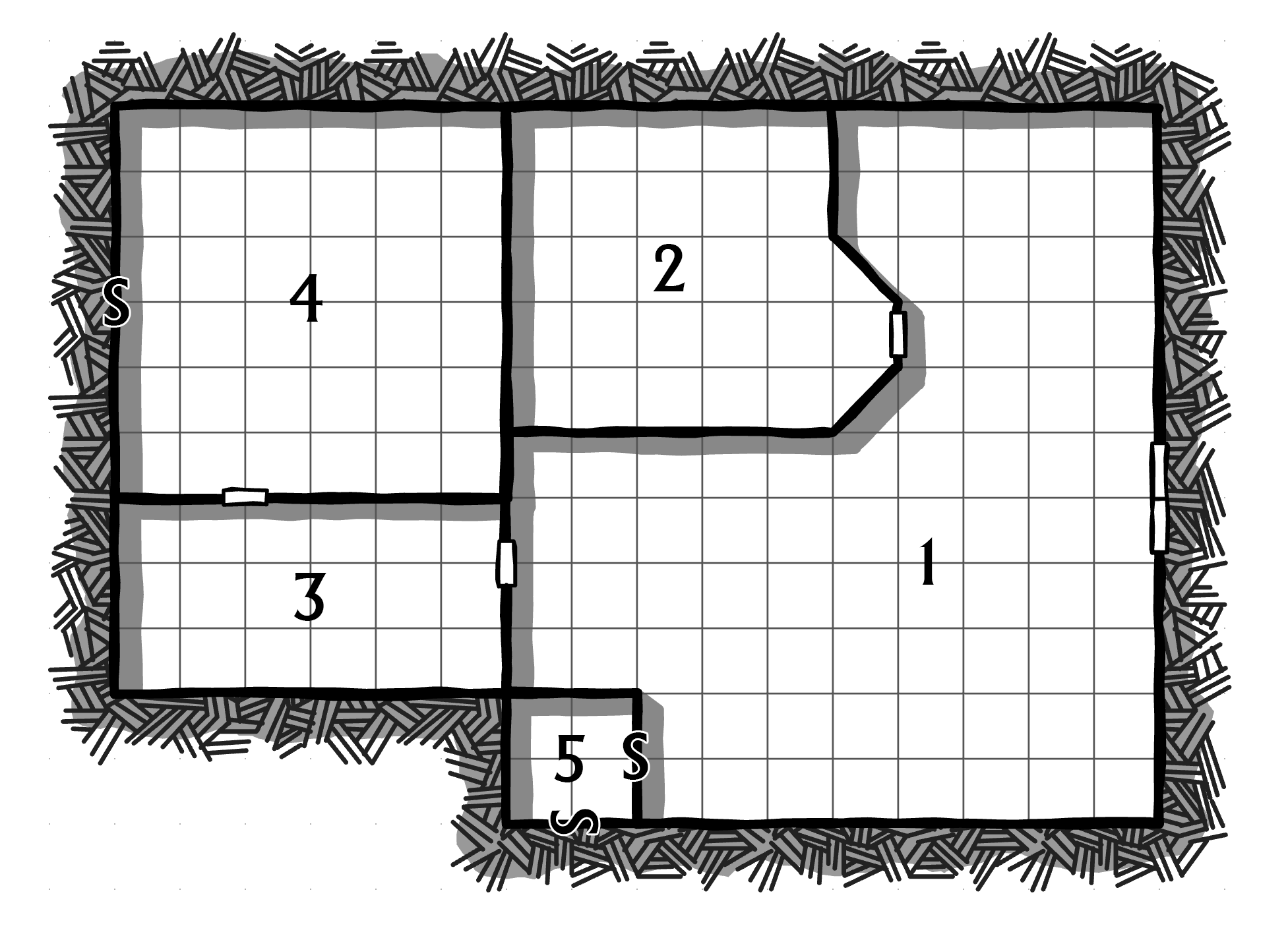

AREA 1 – GOLDSMITHY

Gilted worktables with comfortable seats fill the room.

DAY: There’s roughly 8,000 gp worth of gold strips and 5,000 gp of jewelry in this room. 12 sets of jeweler’s tools.

NIGHT: The tools have been tidied away and the gold strips/jewelry moved to Area 2: Gold Safe.

SAFE DOOR (10-in. iron, to Area 2): AC 19, 300 hp, DC 24 Dexterity (Thieves’ Tools). An alarm spell is keyed to Guildmaster Telidor.

SECRET DOOR: DC 30 Intelligence (Investigation) check. The wall is hollow and this section is designed to be unscrewed.

AREA 2 – GOLD SAFE

The safe contains 25 pp, 350 gp, and 1,300 sp. It also contains large, heavy stacks of gold strips totaling 32,000 gp in value.

NIGHT: An additional 8,000 gp in gold strips and 5,000 gp of jewelry (secured from Area 1).

DC 20 Intelligence (Investigation): There is a hidden compartment in the tiled steel floor of the safe. It holds a number of small, mimatched bags containing 3,116 gp, 43,457 sp, and 103,900 cp.

DM Background: This money flows in from all the illegal operations of the Vladaams. After being held here, it’s transferred from the Goldsmiths’ Guild to legitimate banks.

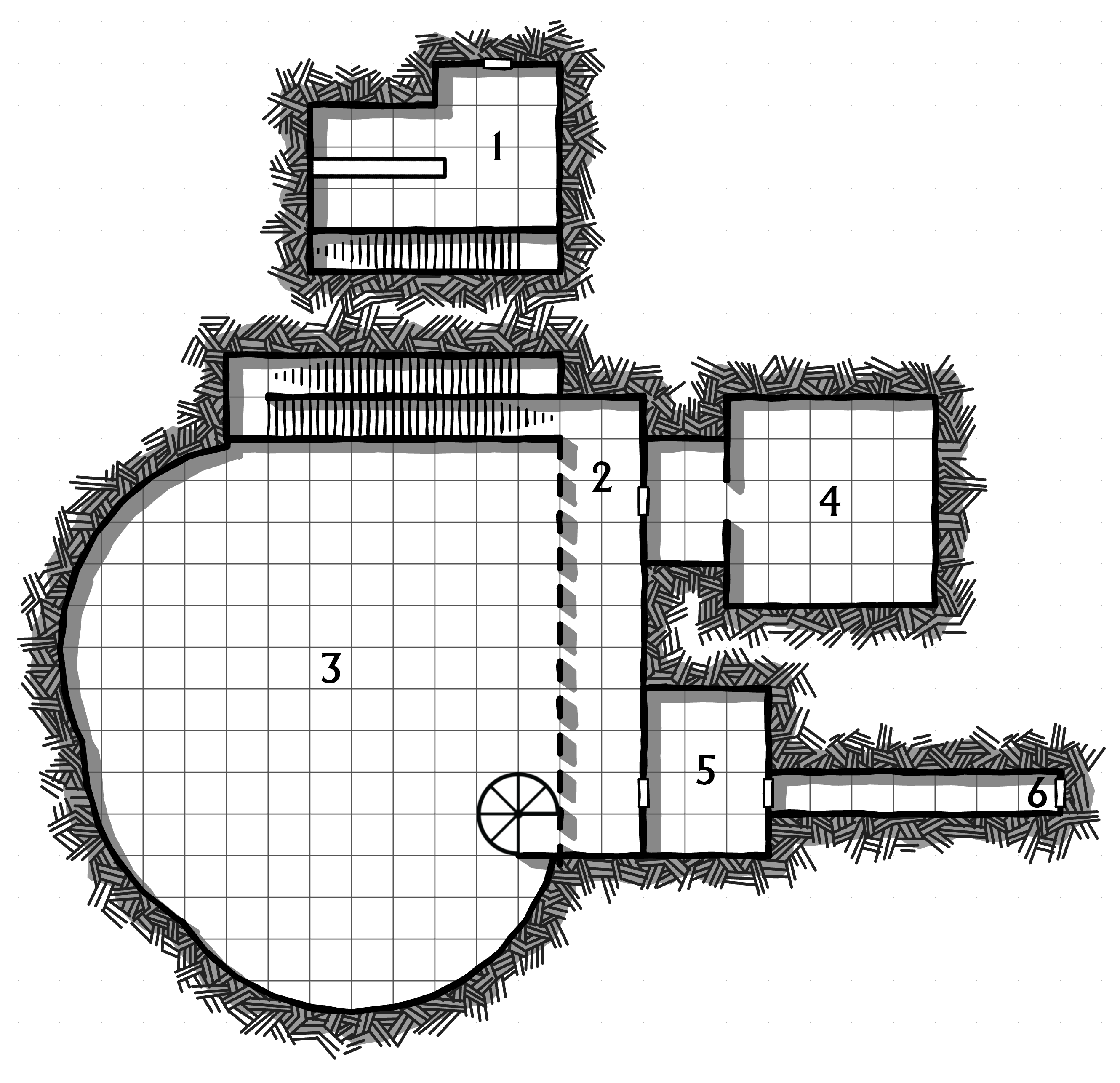

AREA 3 – GUILD GATHERING HALL

A long, heavy table of polished oak runs the length of this room. A chandelier of wrought gold and rubies, lit with continual flame, hangs from the ceiling (5,000 gp value).

AREA 4 – GUILDMASTER’S OFFICE

A tidy, well-sorted desk. A gold inkwell (worth 100 gp) stands on top of the desk.

DESK: Ordinary guild correspondence is neatly stacked in one drawer; blank parchment and quills in another. A third drawer holds a black velvet pouch containing 770 gp.

- DC 14 Intelligence (Investigation): One of the drawers has a false bottom. DC 20 Dexterity (Thieves’ Tools) to open. It contains paperwork relating to the money laundering operations of the guild. There’s usually enough compromising material here to reveal 1d4+2 pieces of uncommon and 1d3 pieces of rare information from the Vladaam gather information tables.

AREA 5 – SMUGGLING HOLE

This appears to be a small, dusty, and forgotten room with a dirt floor.

DC 24 Intelligence (Investigation): Scraping away about a half inch of dirt reveals a trap door leading down to a tunnel which leads under the city wall and emerges about 500 feet away in a small copse of trees.

DM Background: This smuggling hole has not seen much use in recent years. (The Vladaams don’t want to attract unnecessary attention to a guild that’s very successfully laundering their money. But the Guildmaster and a few others in the guild are aware of its existence.)

GUILDMASTER TELIDOR

A striking woman with long black hair plaited with golden wire. She wears a beautiful golden necklace depicting a phoenix being consumed by flames formed from three large and several small red-gold tourmalines (3,000 gp). She also has a pair of matching bracelets, which are actually bracelets of friends (keyed to Navanna twice, Gattara once, Godfred once, Aliastar once, Marcus Corellius twice, and her two bodyguards).

Through her black market work and money laundering with the Vladaams, Telidor has become a very rich woman. As a result, over the past decade her social circle has rapidly escalated. And she likes it. Her ambition has led her to consider buying a familial share in House Abanar in order to raise her star even higher; the only thing holding her back is a fear of retaliation from the Vladaams.

Guildmaster Telidor: Use knight stats, MM p. 347, except she uses a cudgel (1d8+3 bludgeoning) and hand crossbow (1d6 piercing) for her attacks and she has Wisdom 15 (+2).

- Proficiency (+2): Jeweler’s Tools

- Equipment: bracelet of friends (x2), phoenix necklace (3,000 gp), diamond ring (250 gp), Vladaam deot ring

- Bracelet of Friends: This silver charm bracelet has four charms upon it when created. As a bonus action, the owner may designate one person known to them to be keyed to one charm. When a charm is grasped and the name of the keyed individual is spoken as an action, that person is called to the spot, along with their gear, as long as the owner and the called person are on the same plane. The keyed individual knows who is calling, and the bracelet functions only on willing travelers. Once a charm is activated, it disappears. Charms separated from the bracelet are worthless.

Telidor’s Bodyguards (Harla & Jarla): Female lizardfolk. Use gladiator stats, MM p. 348.

- Proficiency (+3): Perception, Stealth, Survival

- Equipment: flaming claw tips (Harla) / frost claw tips (Jarla), javelin of lightning (x2), potion of superior healing, Vladaam deot ring

- Bite. Melee Weapon Attack: +7 to hit, reach 5 ft., one target. Hit: 7 (1d6+4) piercing damage.

- Hold Breath. Lizardfolk can hold their breath for 15 minutes.

- Flaming Claw Tips: +1 to attacks and +2d6 fire damage.

- Frost Claw Tips: +1 to attacks and +2d6 cold damage.