Continuing our “Fun With Vornheim” series from yesterday, today I’m going to use two of the tools included in Vornheim to create a drama-filled scenario.

Continuing our “Fun With Vornheim” series from yesterday, today I’m going to use two of the tools included in Vornheim to create a drama-filled scenario.

First, I’m going to use the “Aristocrats” table on page 46 to create four unique nobles:

- Kyle the Exquisite, who has a peculiar fondness for injured women.

- Lady Orchid the Decapitator, who only derives pleasure from others’ fear.

- Clarissa the Cleaver, who believes the city to be a living entity hostile to her.

- Sasha the Immense, who wants to kill her sister.

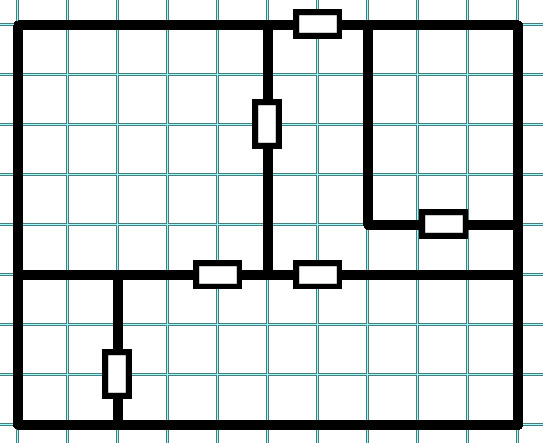

Now I flip to the “Connections Between NPCs” chart on page 53 and use it to determine that:

Kyle the Exquisite:

- Is attracted to Sasha the Immense.

- Secretly disguises himself as Clarissa.

Lady Orchid:

- Frightens Clarissa, who believes her to be an agent of the living city.

- Has befriended Kyle the Exquisite.

Clarissa the Cleaver:

- Is Sasha’s sister.

Sasha the Immense:

- Is suspicious of Lady Orchid.

INTERPRETATION AND EXTRAPOLATION

That gives us quite a lot of juicy material, obviously. How can we interpret it and extrapolate from it?

Kyle the Exquisite is a young and decadent nobleman who has been placed in charge of the city’s executioners, who are also known as the Three Grim Ladies: Orchid, Clarissa, and Sasha. He magically disguises himself as Clarissa in order to be near to Sasha, who he secretly loves.

Sasha, who stands eight feet tall due to the giant’s blood in her, doesn’t know about Kyle’s disguise and is incredibly jealous of her sister (who she believes wants to steal Kyle’s affections).

Clarissa gives every appearance of being a beautiful, delicate flower. Many believe that she has been forced into this line of work by her cruel half-sister, Sasha. But the truth is that her timid veneer merely disguises a crazed bloodlust. Recently she has taken to drinking the blood of the prisoners she executes, and these primitive blood rituals have, in fact, connected her to the malevolent Spirit of the City.

Lady Orchid, a minor noblewoman who has been sentenced to duties of penance as an executioner in order to shame her father, has befriended Lord Kyle who is the only person of her true rank she is allowed to associate with. She is right to fear Clarissa, however: The City wants her and her entire family dead.