Most RPGs use turn-based combat because it can provide a simple method for clearly resolving the chaotic realities of the battlefield. (Simultaneous action resolution, for example, can work really well with very small numbers of combatants, but then breaks down rapidly as the number of combatants increases.)

Turn-based combat, however, creates mechanical oddities: If you were in a swordfight with someone and they were like, “Hang on a sec. I’m just going to grab a pint and have a quick drink,” you’d just stab their dumb ass. But because we’re using an abstract mechanical structure in which everyone resolves their actions one at a time — even though, in reality, everything is happening simultaneously — suddenly you’re just supposed to stand there watching me take my drink because it’s not your turn.

To deal with this, we add off-turn mechanics that allow characters to react to things that they should, logically, be able to react to, even if it isn’t their turn. In D&D 5th Edition, these mechanics include the Ready action, reactions, and opportunity attacks.

We can add one more level to this by adding mechanics that allow you to, for example, avoid opportunity attacks. We might want to do this because a character is super-skilled at drinking in the middle of combat, or maybe just because it’s a bad-ass moment. (The Disengage action in D&D 5th Edition is technically one example of this. In D&D 3rd Edition you could make Tumbling checks to avoid attacks of opportunity from movement and Concentration checks to avoid provoking while casting a spell.)

D&D 3rd Edition sought to implement a lot of mechanics from previous editions of the game in ways that were both more consistent and comprehensive. This included inventing the term “attacks of opportunity” and classifying which actions would “provoke an attack of opportunity.” This made sense, but in practice it had a major drawback: It created a huge list that filled nearly two full pages of actions detailing which actions did (and did not) trigger attacks of opportunity, and you either had to reference that list constantly during play or you had to memorize it. Even if most of this list boiled down to common sense, the result was still Byzantine and arcane.

As a result, after 3rd Edition, there was a practical impulse to avoid this “grand and unwieldy list” of actions. In D&D 5th Edition, this simplification has been taken to an extreme: An opportunity attack is triggered only when a combatant you can see moves out of your reach, unless they take the Disengage action.

This eliminates the complexity of the list by boiling the mechanic down to a single trigger, but it allows a lot of immersion-breaking shenanigans on the battlefield. And even the implementation of the movement-based trigger is kinda wonky: You can literally run circles around an opponent while firing arrows at someone on the opposite side of the battlefield, but you can’t walk past them while swinging your sword at them. And, bizarrely, this means that creatures with longer reach are actually less effective at attacking people around them.

In my opinion, if you wanted to simplify opportunity attacks, it would be preferable to either (a) eliminate the mechanic entirely (can’t get simpler that that!); or (b) go the other direction.

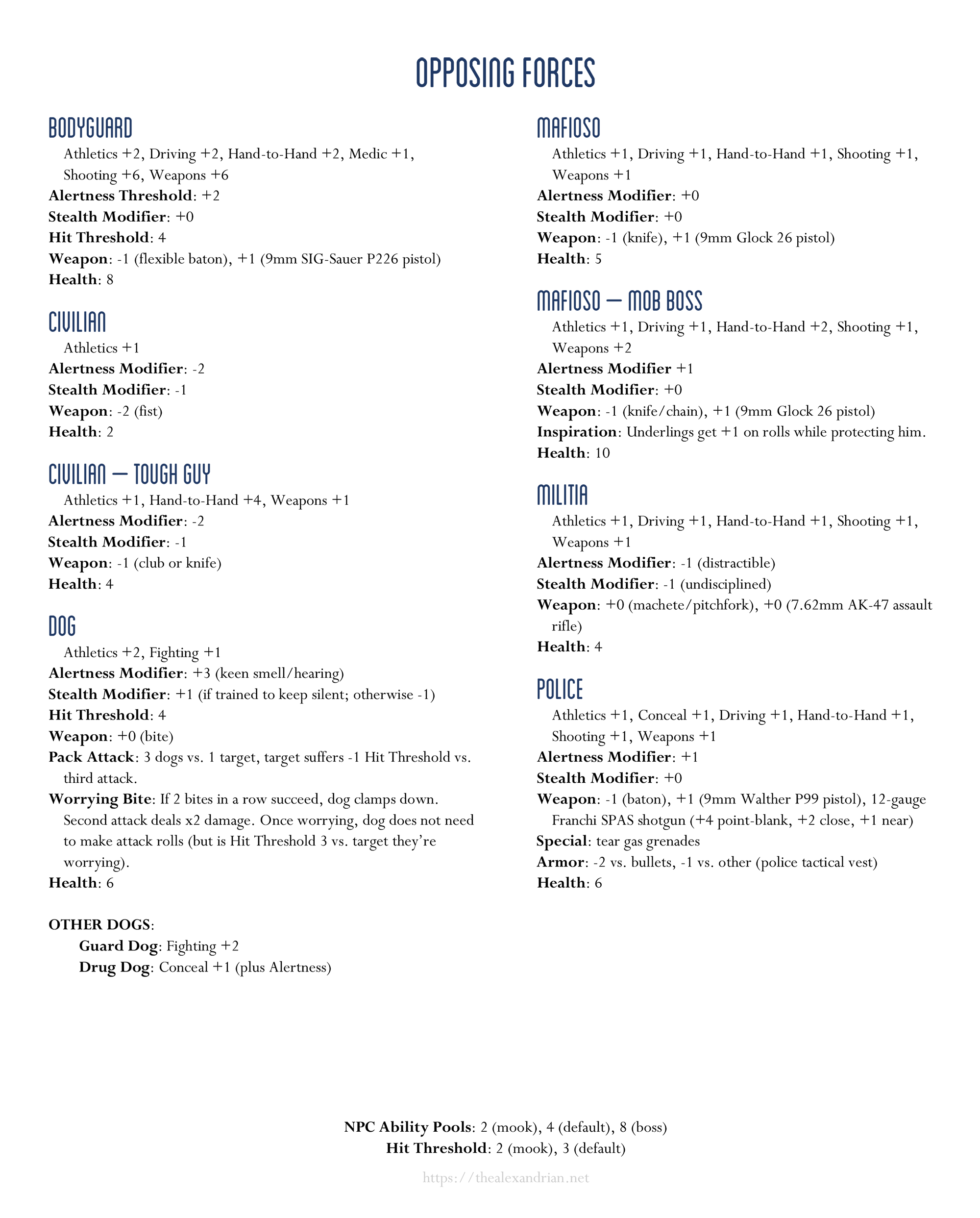

HARDCORE OPPORTUNITY ATTACKS

By default, any action you take provokes an opportunity attack from any combatant who can reach you.

There are three exceptions:

- Any attack action

- Dodge

- Disengage

In addition, Ready doesn’t provoke, but the action you’re readying may provoke when you take it.

Bonus actions, reactions (other than readied actions), and your free object interaction never provoke opportunity attacks.

Movement provokes opportunity attacks normally.

OPTION: BETTER MOVEMENT OAs

When using this option, movement provokes an opportunity attack whenever a character moves more than 5 ft. within your reach on their turn or moves out of your reach.

Note: Disengage still cancels all movement-based opportunity attacks during your turn. You also don’t provoke an opportunity attack when you teleport or when someone or something moves you without using your movement, action, or reaction.

OPTION: DAMAGE SPELLS

Spellcasters can use their bonus action to avoid the opportunity attack triggered by casting a spell if the spell deals damage.

Note: This rule may be useful to make some 5th Edition spells work properly. It avoids needing to make all of those spells special case exceptions. Our goal remains One Rule to Rule Them All.

OPTION: HARDCORE RANGED ATTACKS

Using this option, only melee attack actions avoid opportunity attacks. Ranged attacks still provoke.

Note: As with a spellcaster, you might allow a ranged attacker to use their bonus action to negate the opportunity attack.

DESIGN NOTES

Positioning in combat should matter. You want your rogue to pick the lock on the door so you can all escape? Cover their back! You want your spellcaster to rain hellfire down on your foes? Form a defensive line and give them the space they need to do it.

By allowing characters to just do whatever wherever, the 5th Edition opportunity attack rules cheapen positioning.

Beyond making the battlefield a more interesting space for tactical challenges, I also want things to make sense: If you’re going to do something that isn’t directly focused on fighting, I want you to think to yourself, “Should I really be doing this where the guy with the pointy metal can stab me?”

At the same time, we want to avoid a bunch of Byzantine complexity. We don’t want a big list of what does and does not trigger an opportunity attack: What we want is a simple, straightforward rule that we can easily memorize and apply. We want One Rule to Rule Them All. By flipping things around and listing the very small list of things that DON’T provoke, we achieve that goal.

From a practical point of view, if we end up in a situation where this One Rule to Rule Them All doesn’t make sense, it’s much easier for me as a DM for me to “break” the rules with a ruling that’s more permissive to the PCs than one that isn’t. In other words, saying, “Actually, it would make a lot of sense if this thing you’re doing that would normally provoke doesn’t provoke in this situation,” the players will be much happier accepting that than if I have to say, “Actually, this thing you thought wouldn’t be bad for you is actually going to be bad for you.” A restrictive framing, therefore, can paradoxically give us a greater liberty to make bespoke rulings when and if they’re needed.

ADVANCED DESIGN NOTES

Taking a step back from opportunity attacks, there are two different broad approaches to modeling the idea that you can’t just run willy-nilly around a battlefield or do a crocheting project in the middle of a melee without consequences.

First, you can try to mechanically enforce it: Thou shalt not.

Thou shalt not move past someone threatening you with a melee weapon. Thou shalt not drink a potion if someone has marked you as their target. Thou shalt not run through an area under the effects of suppressive fire.

(My house rules for combat in 1974 D&D, where the procedure effectively makes melee “sticky,” is another approach to this.)

You can also mitigate this approach: Thou shalt not X, unless Y.

For example: “You can move through a threatened space if you succeed on an Acrobatics check.” Or, “If you get hit with an opportunity attack, you have to stop moving.” (If you can avoid the attack, then you can ignore the Thou Shalt Not.)

The other approach is that you can impose a cost for doing it — e.g., “You can do X, but you’ll suffer a penalty.” Or risk getting hit by an extra attack. Or lose an action.

This approach gives more flexibility: If you really want or need to do something, you can still do it. You just have to pay the cost.

And, once again, you can add conditionals that allow characters to mitigate or entirely avoid these costs.

Of course, the highest the cost becomes, the greater your need or desire would need to be to endure it. Conversely, the more negligible the cost becomes, the less influence it will have over the characters’ decisions.

If you think about opportunity attacks within this design paradigm, 5th Edition’s opportunity attacks are clearly aiming for the second method, and my argument is that they have become so trivial that you would be better off either (a) eliminating them entirely in order to streamline combat and encourage even more movement on the battlefield or (b) using the hardcore opportunity attacks house rules (or something like them) to make them actually matter.

Alternatively, you could abandon that paradigm entirely and maybe try to implement something of the Thou Shalt Not variety.