IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

Session 6B: Return to the Depths

In which a sheen of blood signals terrors from beyond the grave, and numerous clothes are ruined much to Tee’s dismay…

This installment of Running the Campaign is going to discuss some specific details of The Complex of Zombies, so I’m going to throw up a

This installment of Running the Campaign is going to discuss some specific details of The Complex of Zombies, so I’m going to throw up a

SPOILER WARNING

for that published adventure. (Although I guess if you’ve already read this week’s campaign journal, the cat is kind of out of the bag in any case.)

Interesting conundrum:

- D&D has zombies.

- D&D can’t take advantage of the current (and long ongoing) craze for zombie stuff.

Why? Because zombies in D&D were designed as the patsies of the undead world. In the early 1970’s, when Arneson and Gygax were adding undead to their games, zombies were turgid, lumbering corpses that had been yanked out of a fairly obscure film called Night of the Living Dead. (Even Romero’s sequels wouldn’t arrive until 1978, and modern zombie fiction in general wouldn’t explode until the ‘80s.) Even skeletons, backed up by awesome Harryhausen stop-motion animation, were much cooler and had more cultural cachet.

From a mechanical standpoint, the biggest problem zombies have is their slow speed. In AD&D this rule was, “Zombies are slow, always striking last.” (Although in 1st Edition they were probably better than they would ever be otherwise, as their immunity to morale loss was significant.) The 3rd Edition modeling of this slow speed, however, was absolutely crippling: “Single Actions Only (Ex): Zombies have poor reflexes and can perform only a single move action or attack action each round.”

They were further hurt by a glitch in the 3rd Edition CR/EL system: The challenge ratings for undead creatures were calculated using the same guidelines as for all other creatures. But unlike all other creatures, undead (and only undead) could be pulverized en masse by the cleric’s turn ability. This meant that undead in general were already pushovers compared to any comparable opponent, and zombies (which were pushovers compared to other undead) were a complete joke.

(The general problem with undead was, in my opinion, so limiting for scenario design in 3rd Edition that I created a set of house rules for turning to fix the problem. There’s some evidence that these house rules are actually closer to how turning originally worked at Arneson’s table.)

In short, you could have a shambling horde of zombies (as long as the horde wasn’t too big), but it wouldn’t be frightening in any way.

Which is kind of a problem, since “horror” is literally what the whole zombie shtick is supposed to be about.

REINVENTING ZOMBIES

My primary design goal with The Complex of Zombies scenario was, in fact, to reinvent the D&D zombie into something which would legitimately strike terror into the hearts of PCs. James Hargrove described the result as, “… more or less Resident Evil in fantasy. Which rocks. And it rocks because it’s not just zombies but zombie-like things. Bad things. Bad things that eat people. Bad things that are just different enough from bog standard zombies to scare the crap out of players when they first encounter them.” Which I absolutely thrilled at seeing, because that’s exactly what I was shooting for.

One could, of course, simply have gone with a souped up “fast zombie, add turn resistance”. But I wanted to do more than that. I wanted to create a zombie-like creature that would actually instill panic at the gaming table. And the key to that was the bloodwight and its bloodsheen ability:

Bloodsheen (Su): A living creature within 30 feet of a dessicated bloodwight must succeed at a Fortitude save (DC 13) or begin sweating blood (covering their skin in a sheen of blood). Characters affected by bloodsheen suffer 1d4 points of damage, plus 1 point of damage for each bloodwight within 30 feet. A character is only affected by bloodsheen once per round, regardless of how many bloodwights are present. (The save DC is Charisma-based.)

Because the bloodsheen was coupled to a health soak ability that slowly transformed desiccated bloodwights into lesser bloodwights, the resulting creature combined both slow and fast zombies into a single package. The bloodsheen itself was not only extremely creepy, but also presented a terrifying mystery (since it would often manifest before the PCs had actually seen the bloodwight causing it).

Eventually, of course, the players should be able to figure out what’s happening and be able to put a plan of action in place to deal with it. (“Cleric in front, preemptive turning.” will cover most of your bases here.) But the design of The Complex of Zombies is designed to occasionally baffle or complicate these tactics.

Which, in closing, also brings me to another important point about using scenario design advice: I’ve had a couple different people who purchased The Complex of Zombies contact me and say, “Hey! Why isn’t this dungeon heavily xandered? Isn’t that your thing?”

Well, no. My thing is designing effective dungeons.

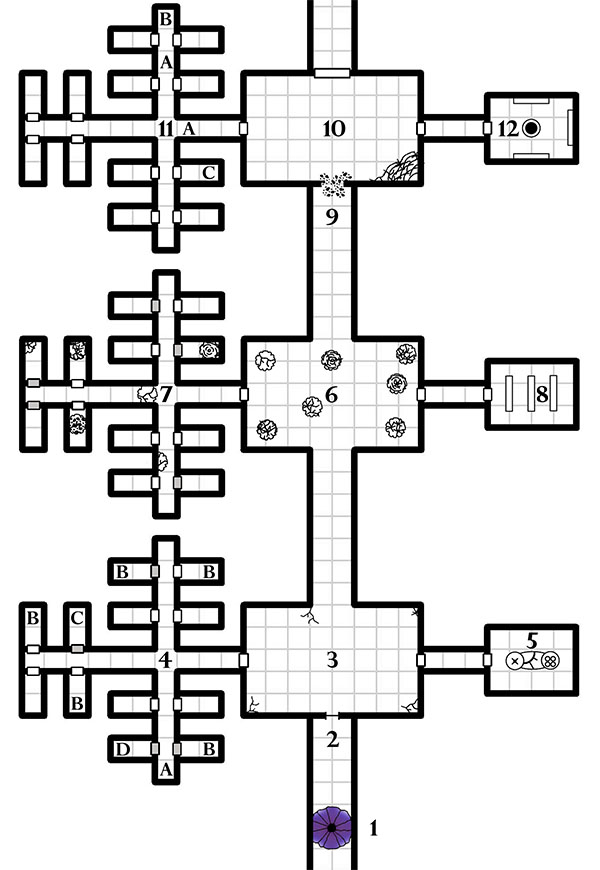

The Complex of Zombies uses a claustrophobic, branching design in order to amp up the terror. Multiple doors create “airlocks” that prevent you from seeing what’s ahead, but also cause you to lose sight of what’s behind you. Its largely symmetrical design creates familiarity and allows the PCs to benefit from “unearned” geographic knowledge, but that familiarity is subverted with terrible, hidden mysteries so that the familiar becomes dangerous. The progressive, three-layered depth of the complex meant that every step forward felt like a deeper and deeper commitment to the horrific situation. Finally, virtually every navigational decision meant turning your back on a door. (And the myriad number of doors became daunting in and of itself when the bloodsheen could be coming from behind any one of them.)

There was one stage in design where I considered linking Area 4 and Area 11 with some form of secret passage. But there are only three possible uses of such a passage:

- The players use it to “skip ahead”, which wouldn’t really give them any significant geographical advantage due to the nature of the scenario, but would disrupt the “pushing deeper, committing more” theme of the scenario. (I wanted depth in the dungeon’s design and this would have flattened the topography.)

- The players miss the first instance of the passage, but find the second. After a moment of excitement, they end up backtracking to an earlier part of the dungeon, which in most instances is going to be accompanied by the “wah-wah” of a sad trombone sounding the anti-climax as they trudge back to where they were and continue on.

- The bloodwights could use it to circle around behind the PCs and ambush them. The bloodwights were so deadly, however, that a clear line of retreat was really kind of essential for the whole scenario not to become a TPK. (There’s still a risk of this happening if the PCs don’t play smart, but that’s on the players.)

To sum up: Design guidelines are rules of thumb. Following them blindly or religiously is not always for the best. In this case, minimal xandering was the right choice to highlight the terrors of the bloodwights.