There are two different GMing techniques that can be referred to as “choose your own adventure”.

(If you’re on the younger side and have no idea what I’m talking about, the Choose Your Own Adventure Books, which have recently been brought back into print, were a really big thing in the ‘80s and ‘90s. They created the gamebook genre, which generally had the reader make a choice every 1-3 pages about what the main character — often presented as the reader themselves in the second person — should do next, and then instructing them about which page to turn to continue the story as if that choice had been made.)

(For those on the older side: Yes, I really did need to include that explanation.)

The first technique happens during scenario prep. The GM looks at a given situation and says, “The players could do A or B, so I’ll specifically prep what happens if they make either choice.” And then they say, “If they choose A, then C or D happens. So I’ll prep C and D. And if they choose B, then E or F could happen, so I’ll prep E and F.”

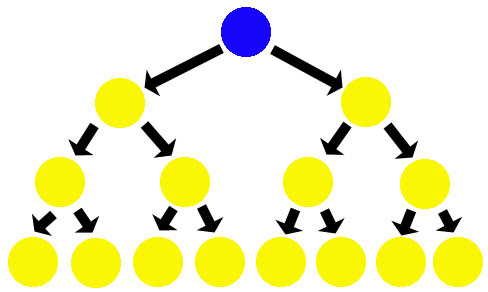

And what they end up with looks like this:

This is a bad technique. First, because it wastes a ton of prep. (As soon as the players choose Option A, everything the GM preps down the path of Option B becomes irrelevant.) Second, because the players can render it ALL irrelevant the minute they think of something the GM hasn’t anticipated and go with Option X instead. (Which, in turn, encourages the GM to railroad them in order to avoid throwing away their prep.)

The problem is that the GM is trying to pre-run the material. This is inherently a waste of time, because the best time to actually run the material is at the table with your players.

But I’ve written multiple articles about this (most notably Don’t Prep Plots and Node-Based Scenario Design), and it’s also somewhat outside the scope of this series.

What I’m interested in talking about today is the second variety of Choose Your Own Adventure technique, which I suppose we could call:

RUN-TIME CHOOSE YOUR OWN ADVENTURE

GM: You see that the wolf’s fur is matted and mangy, clinging to ribs which jut out through scrawny skin. There’s a nasty cut along its flank. It snarls menacingly at you. Do you want to attack it? You could also try offering it some food.

With run-time choose your own adventure, in addition to describing a particular situation, the GM will also offer up a menu of options for how the players can respond to it. In milder versions, the GM will wait a bit (allowing players to talk through a few options on their own) before throwing in his two cents. In the cancerous version, the GM will wait until a player has actually declared a course of action and then offer them a list of other alternatives (as if to say, “It’s cute that you thought you had autonomy here, but that’s a terrible idea. Here are some other options you would have come up with if you didn’t suck.”).

It can be an easy trap for a GM to fall into because, when you set a challenge for the PCs, you should be giving some thought to whether or not it’s soluble, and that inherently means thinking through possible solutions. It’s often very easy to just burble those thoughts out as they occur to you.

It’s also an easy trap to fall into during planning sessions. Everyone at the table is collaborating and brainstorming, and you instinctively want to jump into that maelstrom of ideas. “Oh! You know what you could do that would be really cool?”

It’s also an easy trap to fall into during planning sessions. Everyone at the table is collaborating and brainstorming, and you instinctively want to jump into that maelstrom of ideas. “Oh! You know what you could do that would be really cool?”

But you have to recognize your privileged (and empowered) position as the GM. You are not an equal participant in that brainstorming:

- As an arbiter of whether or not the chosen action will succeed, you speak with an inherent (and, in many cases, overwhelming) bias.

- You’ve usually had a lot more time to think about the situation that’s being presented (or at least the elements that make up that situation), which gives you an unfair advantage.

- You often have access to information about the scenario that the players do not, warping your perception of their decision-making process.

The players, through their characters, are actually present in the moment and the ideas they present are being presented in that moment. The ideas that you present are interjections from the metagame and disrupt the narrative flow of the game.

Because of all of this, when preemptively suggesting courses of action, you are shutting down the natural brainstorming process rather than enabling it (and, in the process, killing potentially brilliant ideas before they’re ever given birth). And if you attempt to supplement the options generated by the players, you are inherently suggesting that the options they’ve come up with aren’t good enough and that they need to do something else.

So, at the end of the day, you have to muzzle yourself: Your role as the GM is to present the situation/challenge. You have to let the players be free to fulfill their role, which is to come up with the responses and solutions to what you’ve created.

As the Czege Principle states, “When one person is the author of both the character’s adversity and its resolution, play isn’t fun.”

But more than that, when you liberate the players to freely respond to the situations you create, you’ll discover that they’ll create new situations for you to respond to (either directly or through the personas of your NPCs). And that’s when you’ll have the opportunity to engage in the same exhilarating process of problem-solving and roleplaying, discovering that the synergy between your liberated creativity and their liberated creativity is greater than anything you could have created separately.

WITH NEW PLAYERS

This technique appears to be particularly appealing to GMs who are interacting with players new to roleplaying games. The thought process seems to be that, because they’re new to RPGs, they need a “helping hand” to figure out what they should be doing.

In my experience, this is generally the wrong approach. It’s like trying to introduce new players to a cooperative board game by alpha-quarterbacking them. The problem is that you’re introducing them to a version of a “roleplaying game” which features the same preprogrammed constraints of a board game or a computer game, rather than exposing them to the element which makes a roleplaying game utterly unique — the ability to do anything.

What you actually need to do, in my general experience, is to sit back even farther and give the new players plenty of time to think things through on their own; and explicitly empower them to come up with their own ideas instead of presenting them with a menu of options.

This does not, of course, mean that you should leave them stymied in confusion or frustration. There is a very fine line that needs to be navigated, however, between instruction and prescription. You can stay on the right side of that line, generally speaking, by framing conversations through Socratic questioning rather than declarative statements: Ask them what they want to do and then discuss ways that they can do that, rather than leading with a list of things you think they might be interested in doing.

WITH EXPERIENCED PLAYERS

You can, of course, run into similar situations with experienced players, where the group has stymied itself and can’t figure out what to do next. When you’re confronted with this, however, the same general type of solution applies:

A few things you can do instead of pushing your own agenda:

- Ask the players to summarize what they feel their options are.

- In mystery scenarios, encourage the players to review the evidence that they have. (Although you have to be careful here; you can fall into a similar trap by preferentially focusing their attention on certain pieces of information. It’s really important, in my experience, for players in mystery scenarios to draw their own conclusions instead of feeling as if solutions are being handed to them.)

- If they’ve completely run out of ideas, bring in a proactive scenario element to give them new leads or new scenario hooks to follow up on.

Also: This sort of thing should be a rare occurrence. If it’s happening frequently, you should check your scenario design. Insufficient clues in mystery scenarios and insufficient scenario hooks in sandbox set-ups seem to be the most common failure points here.

This problem can also be easily mistaken for the closely related situation where the group has too many options and they’ve gotten themselves locked into analysis paralysis. When this happens, it should be fairly obvious that tossing even more options into the mix isn’t going to solve the problem. A couple things you can do here (in addition to the techniques above, which also frequently work):

- Simply set a metagame time limit for making a decision. (Err on the side of caution with this, however, as it can be very heavy-handed.)

- Offer the suggestion that they could split up and deal with multiple problems / accomplish multiple things at the same time.

The latter would seem to cross over into the territory of the GM suggesting a particular course of action. And that’s fair. But I find this is often necessary because a great many players have been trained to consider “Don’t Split the Party” as an unspoken rule, due to either abusive experiences with previous GMs or more explicitly from previous GMs who don’t want to deal with a split party. That unspoken rule is biasing their decision making process in a manner very similar to the GM suggesting courses of action, and the limitations it imposes often result in these “analysis paralysis” situations where they want to deal with multiple problems at the same time, but feel that they can’t. Explicitly removing this bias, therefore, solves the problem.

You can actually encounter a similar form of analysis paralysis where the players feel that the GM is saying “you should do X”, but they really don’t want to. Or they’d much rather be doing Y. And so they lock up on the decision point instead of moving past.

Which, of course, circles us back to the central point here: Don’t put your players in that situation to begin with.

Great Arkham.

Great Arkham.