IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

SESSION 25A: THE SECOND END OF GHUL’S LABYRINTH

June 21st, 2008

The 12th Day of Kadal in the 790th Year of the Seyrunian Dynasty

They stepped forward into Elestra’s sanctuary. The wall closed behind them, transforming itself into a fireplace with a crackling fire already lit. Directly above the fire, a mirror was hung.

“What is this place?” Tee asked.

“A secret,” Elestra said, looking around with a sense of vague familiarity overwhelming her. “I think I’ll be able to open a doorway to this place no matter where we might be. We should be safe here. No one can see the entrance from the outside.”

Ranthir, too, was struck by the familiarity of the place. Following some instinct he turned suddenly towards the mirror above the fire. Touching it, he was surprised to see the mirror’s surface suddenly frost over. When it cleared a moment later, it was a transparent window looking out into the hallway they had just left. They could see the ghulworg skeleton crouched there, waiting patiently for their return.

“What did you do?” Dominic asked, looking slightly alarmed.

“I don’t know…” Ranthir said contemplatively. “It just seemed like the right thing to do…”

“Well, at least this way we don’t have to worry about getting ambushed when we decide to leave,” Agnarr said.

Dominic started poking at random things around the room. “If it worked for Ranthir it might work for me…”

Tee smiled and took over where Dominic left off, giving the room a quick and cursory search without turning up anything of particular interest.

Tor, meanwhile, had counted the beds. There were just enough. “Well, at least I won’t have to bunk with Agnarr again.”

EXPLORING EVERY CORNER

(09/13/790)

The next morning they returned to the stairs and headed down to the second level. There was still one small section of the complex that they had not yet explored: The hallway beyond the torture chamber from which the undead horror with long, blood-sucking claws had come.

There they found a long hall containing a table of black stone and massive, yet elegant, high-backed chairs. There was also a large aubrey of preserved oak containing a large number of silver goblets and three bottles of ancient orcish bloodwine – all perfectly preserved by one of the many preservation spells which had been laid on these halls.

Unfortunately, these preservation spells had turned the next chamber – an office of some sort – into a rather gruesome scene: The large desk on the far side of the room had been smashed into two pieces, which lay upon a once-luxurious carpet which had been horribly stained and soiled… and so laden with blood that it squished beneath their feet.

Fresh blood made them nervous, so Agnarr was nominated to check it out. He found the desk to be nothing but splintered wood, but has he backed away cautiously he suddenly gasped in pain as a sharp blade lacerated his ribs from behind.

A black centurion had silently entered through the far door and taken them all by surprise as it lunged out of the flickering shadows cast by the flames of Agnarr’s sword. There was a moment of fear at the sight of such a deadly opponent… but then they realized that they were still being followed diligently by the ghulworg.

Agnarr backed away from the centurion, carefully parrying its blows. And then the ghulworg leapt in, smashing it to bits in mere moments.

Pushing through the door the centurion had come from, they discovered a small complex essentially identical to the one in which they had fought the other centurions. In fact, several more centurions were already in the process of activating. But their numbers made little difference: The ghulworg made short work of them.

In fact, the group showed such little concern over the matter that Tee was already searching the blood-soaked office before the last centurion fell. In the floor, under the oozing carpet, she found a hidden safe.

A safe meant there might be something particularly valuable. So, with a fair degree of excitement, Tee quickly broke the combination and spun the door of the safe open.

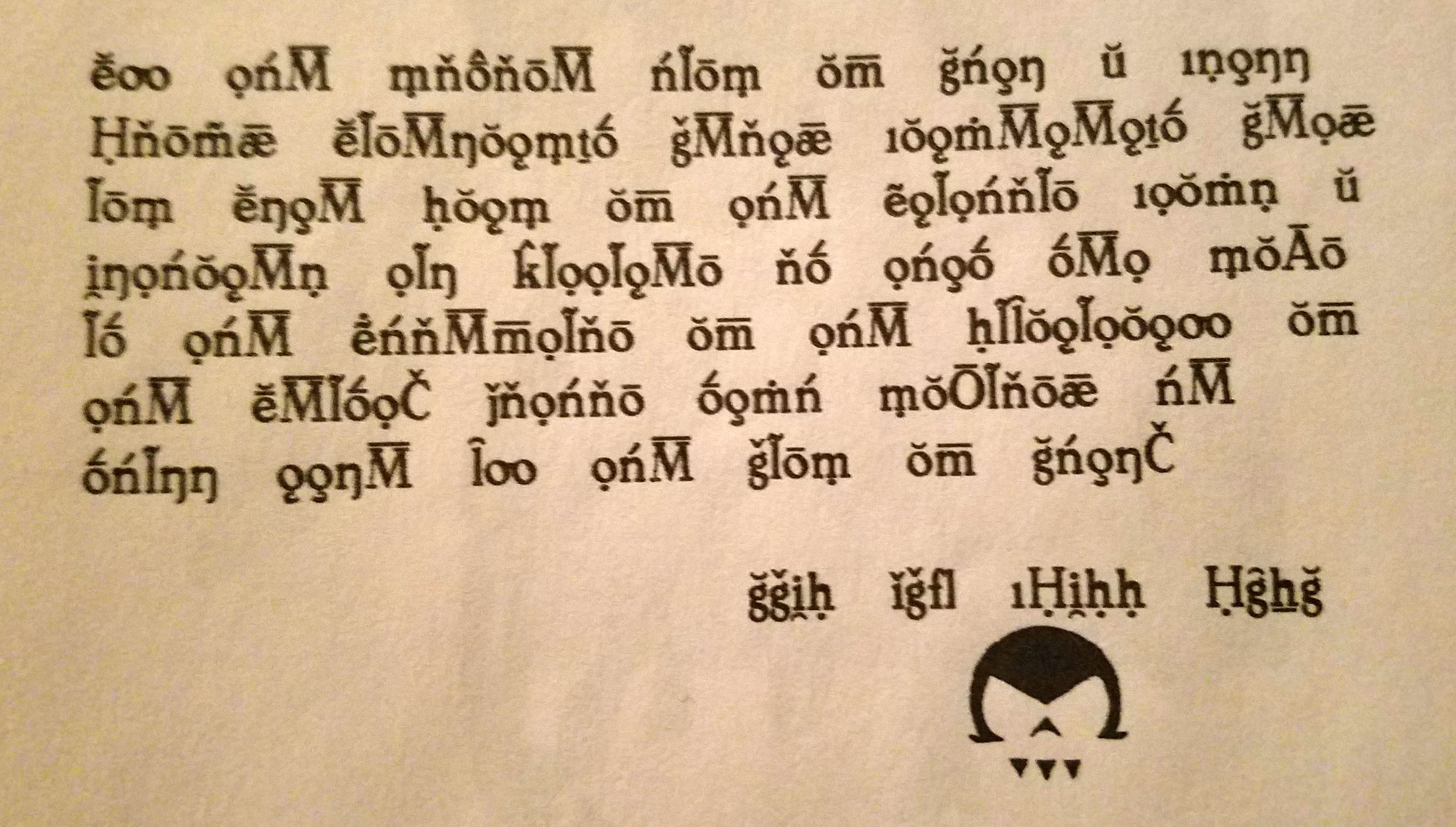

She was somewhat disappointed to discover that the safe was almost entirely empty. The only thing it contained, in fact, was a heavy roll of parchment. Unrolling it she discovered a text of thick, reddish-black Orcish characters. Despite being written in Orcish, the entire document appeared to be elegantly scribed. Near the bottom of the page an immense black seal had been set and impressed in the wax was a familiar skull-shaped sigil. A piece of black-and-gold ribbon had also been attached to the wax.

Tee handed the scroll to Ranthir, who quickly deciphered it using a quick bit of legerdemain:

By the divine hand of Ghul – Skull King, Banelord’s Heir, Sorcerer’s Get, and Blue Lord of the Arathian Stock – Ulthorek tal Yattaren is thus set down as the Chieftain of the Laboratory of the Beast. Within such domain, he shall rule by the Hand of Ghul.

Ghul the Skull King

“Interesting,” Elestra said. “Is it worth anything?”

“If that’s actually Ghul’s signature and seal, it might be worth quite a lot, actually,” Tee said… although she was doubtful that Ranthir would be willing to part with it. (In fact, he had already slipped it into one of his many pouches.)

They were now confident that they had mapped out every corner of the complex (with the exception of whatever might be inaccessible behind the various bluesteel doors they had discovered), which meant that there were only a few loose ends left for them to investigate.

They started with the vault they had unsuccessfully attempted to break into before. The four iron rods, each topped by a ball of brass, still stood in the corners of the room – menacing only because of their vivid memory of the electrical bolts which Agnarr had triggered twice before.

While the others kept to a safe distance, Tee tried to access the vault door using the magical properties of her new ring… but this failed spectacularly, and she only narrowly managed to dodge the worst of the electrical bolts she triggered in the attempt.

With a shrug, Tee got to her feet and left the room. A few moments later, the ghulworg had smashed down the vault doors (although many of its bones were visibly blackened from the electrical storm it suffered in the process).

They were very disappointed, however, to discover that their painful efforts had been in vain. The walls of the iron-shod vault were lined with numerous shelves both large and small, covered with small, carefully-crafted niches which were each clearly designed to hold some unique item. But all of the niches were now empty.

BACK TO THE CLAN CAVES

Which left only the seemingly bottomless pit at the center of the massive, silvery-grey pool.

Using her boots of levitation, Tee “walked” her way across the ceiling above the pool and then dropped down to the walkway circling the pit. Behind her she could hear Elestra trying to convince the others that they should start prying out the glowgems on the ceiling, She shook her head in exasperation and made her way around the edge of the pit, carefully keeping her distance from the familiar brass-tipped rods of iron positioned around the walkway.

Halfway around the perimeter she noticed that a line of pitons had been driven ladder-like into the wall of the pit. Even with her keen elven vision, Tee couldn’t see how far down they might go.

She called out to the others, telling them what she had seen. They decided to see where the pitons might lead. Elestra transformed into a hawk and flew the boots of levitation back and forth, allowing the others to safely cross the pool one at a time.

They climbed down the pitons. After more than a hundred feet, they ended at a narrow fissure that cracked the otherwise smooth sides of the pit.

There was still no bottom in sight below them. Tee, who had taken back her boots of levitation, used them to descend another 500 feet and still couldn’t see any end to the sheer shaft.

She returned to the others and they decided to pursue the path of the pitons. Squeezing through the fissure they worked their way through a series of tight caves that gradually widened as they delved deeper. For awhile they were able to walk in a rather cramped fashion, but then the caves narrowed again and they found themselves crawling for a long while.

At last, they crawled their way out into a larger passage that – as they stood up, brushed themselves off, and stretched – looked rather familiar. Turning to the right, they quickly confirmed their suspicions as they entered a cave with a familiar message written in Goblin upon the wall: “These caves belong to the Clan of the Torn Ear.”

They were surprised, however, to find that the holy symbols of Vehthyl and Itor had been written on the wall directly beneath the familiar greeting.

They were still discussing what this might mean when a goblin entered the cave. They didn’t recognize her, but she certainly recognized them. She told them that she had just come from the fungal farms, but she would be more than happy to take them to Crashekka and Itarek.

Passing through the siege gate, they entered the Great Hall of the clan. Crashekka sat in her place of honor at the far end of the hall, and Itarek stood beside her. They greeted the heroes with wide, toothy grins.

“Welcome, heroes of the world above!” Crashekka said. And then Itarek strode forward and shook their hands, a custom that they had inadvertently taught to him.

Tee carefully asked them about the holy symbols they had seen, not certain of what their reaction might be. But Itarek seemed more than happy to explain. “Our tribe has been touched by the gods of the holy man,” he said, gesturing towards to Dominic (who fidgeted nervously). “I was the first to receive their visions, but many have dreamed their words. And there are greater wonders, too.”

He took them to the maiden’s chambers where Dominic had saved the lives of the tribe’s woman. There he showed them newborn goblins, each bearing a sigil of one of the Nine Gods.

Dominic’s brow furrowed. “Does this mean I need to stay and teach them?”

“I don’t think so,” Tee said, but she couldn’t really keep the concern out of her voice. She wasn’t sure what any of this might mean.

When the question was put to Itarek, he shook his head. “No. I know you have your own path to follow in the world above. And we shall have to find our own path to the Gods’ Truth.”

NEXT:

Running the Campaign: Re-Skinning – Campaign Journal: Session 25B

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index