A couple of years ago David Myers, a media professor at Loyola University, published “Play and Punishment: The Sad and Curious Case of Twixt“. The paper described how Myers conducted a sociology experiment in the City of Heroes MMORPG while playing a character named Twixt. To sum up:

A couple of years ago David Myers, a media professor at Loyola University, published “Play and Punishment: The Sad and Curious Case of Twixt“. The paper described how Myers conducted a sociology experiment in the City of Heroes MMORPG while playing a character named Twixt. To sum up:

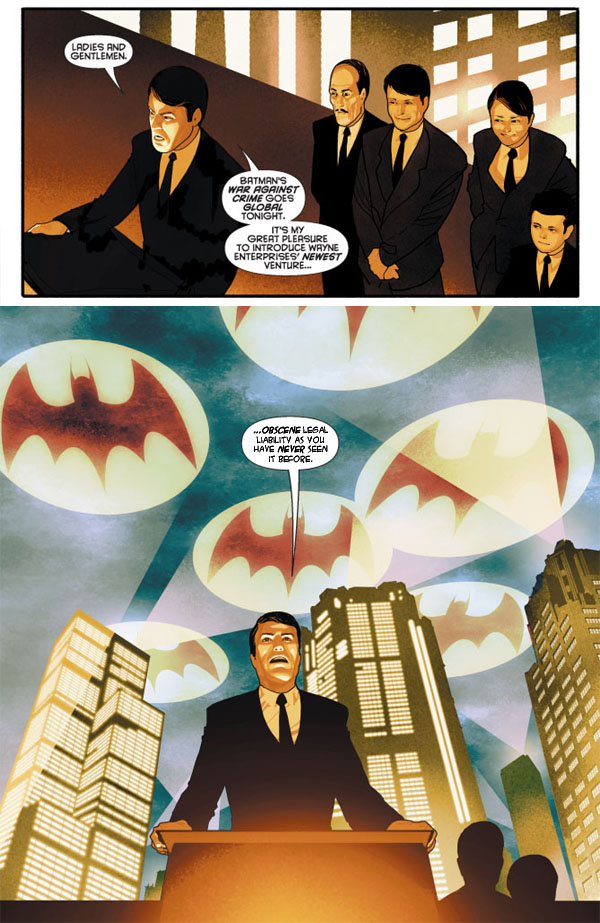

(1) Myers would enter a PVP area in the game and use whatever tactics were legally allowed by the rules of the game in order to win the area.

(2) These included tactics which other players felt were “cheap”, disrupted the normal cross-faction socializing, and/or interfered with non-PVP exploits being used to “farm” the zone.

(3) Other players attempted to force Myers to abandon his tactics by insulting, denigrating, threatening, and/or ostracizing him. (Myers was harassed in the chat channels and forums, expelled from his guild, and even received real-life death threats.)

The conclusion Myers wants to draw from this experiment is simple: “He said his experience demonstrated that modern-day social groups making use of modern-day technology can revert to “medieval and crude” methods in trying to manipulate and control others.”

As he put it in the original paper, “That is, the social order within CoH/V seemed to operate quite independently of game rules and almost solely for the sake of its own preservation. It did not seem within the purview of social orders and ordering within CoH/V to recognize (much less nurture) any sort of rationality — or, for that matter, any supra-social mechanism that might have adjudicated Twixt’s behavior on the basis of its ability to provide, over time, great knowledge of the game system….”

I’m somewhat conflicted.

PLAYING TO WIN

On the one hand, I’m an advocate of Sirlin’s philosophy of Playing to Win. (If you aren’t familiar with it, I highly recommend following that link.) When it comes to purely competitive games — games like Street Fighter 2, Starcraft, Twilight Imperium, or football — those who don’t play to win are clearly engaging in irrational and needlessly self-defeating behavior.

But should the PVP area of an MMORPG necessarily be considered a purely competitive environment?

It certainly can be: For example, the Warsong Gulch mini-game of capture the flag in World of Warcraft takes place in a sequestered game map: The only reason to go there is to enter into a PVP competition.

But the PVP area Myers was competing in presents a more complicated situation: Other players clearly had coherent and rational non-PVP reasons for participating in that area. Myers may have been following the rules of the game, but should that automatically give his agenda priority over the agendas of the other players in the game?

At one level the question really becomes: Why are we playing these games?

And, frankly, I have no doubt that Myers would have found similar responses to his “griefing” tactics even if he had been using them in a completely and indisputably competitive environment. Sirlin elucidates the fundamental nature of scrub behavior, and it’s absolutely trivial to find complaints of “cheap sniper!” or “spawn camper!” in any number of FPS deathmatches. (Although would the responses have become so severely virulent without the accompanying disruption of a social norm? That’s an interesting question.)

But I think there is a deeper failure of self-analysis on the part of Myers.

TWIXT IN THE REAL WORLD

In his paper, Myers writes:

In real-world environments, “natural” laws governing social relationships, if they exist at all, are part of the same social system in which they operate and, for that reason, are difficult to isolate, measure, and confirm. In Twixt’s case, however, two unique sets of rules – one governing the game system, one governing the game society — offered an opportunity to observe how social rules adapt to system rules (or, more speculatively, how social laws might reproduce natural laws.) And, the clearest answer, based on Twixt’s experience, is that they don’t. Rather, if game rules pose some threat to social order, these rules are simply ignored. And further, if some player — like Twixt — decides to explore those rules fully, then that player is shunned, silenced, and, if at all possible, expelled.

Myers assumes that the game rules should naturally define the rules of society. That society, in failing to live by those rules, is acting irrationally.

To analyze the legitimacy of Myers assumption, let’s hypothetically apply Twixt’s behavior to the real world:

Twixt enters a small town. He sees a woman he desires, so he rapes her. He then moves on to other women and begins raping them, one after another. The people of the town don’t like what Twixt is doing: Attempts to physically restrain or kill him fail (either because he’s too strong or perhaps they are unarmed while he has a gun), so he quickly finds himself ostracized from society. People avoid him, and when they can’t avoid him they try to shame him into changing his behavior.

From Twixt’s point of view he’s playing by the rules of reality: The system is clearly set up to reward mass procreation and a wide “sowing of the seed”. Nor is he breaking any natural laws of reality. In fact, people keep praying to God for Twixt to stop and God never does anything to stop him. That only proves that Twixt is playing by the rules. (Myers specifically uses the fact that the GMs in City of Heroes didn’t punish his behavior as indicative that his behavior was within the rules of the game.)

Twixt is just “exploring those rules fully”. And Myers apparently expects us to consider the efforts of the townsfolk to have Twixt “shunned, silenced, and, if at all possible, expelled” to be “medieval and crude”.

But I think we can all agree that Twixt the Serial Rapist should be punished and ostracized by society.

Myers writes, “If either natural or system laws governing social order in the real world are in any way analogous to the game rule sof the COH/V virtual world, we can conclude that social orders in general are more likely to deny than reveal those laws.” He goes on to say that this denial “seems drastically and overly harsh, even unnatural“.

But the very nature of society is to deny the primacy of natural law. “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law” has been pretty consistently shown to be a spectacularly crappy philosophy (as Twixt the Serial Rapist demonstrates). A healthy society, on the other hand, tends to operate on the principle that “your freedom ends where my nose begins”.

Myers, on the other hand, seems to willfully ignore the fact that his flailing hands are smashing into people’s noses.

IN CONCLUSION

But while I find Myers’ general conclusions regarding the function of society to be wrong-headed, I remain conflicted regarding the specific example of behavior in City of Heroes.

While “your freedom ends where my nose begins” is a relatively solid philosophy in the real world, we obviously set it aside when we sit down to play a competitive game. (Football, for example, would be a relatively boring game if all the players politely agreed not to invade each others’ personal space.) In fact, I would argue that one of the things that makes a game appealing is specifically the fact that it constitutes a safe environment in which we agree to abandon certain social norms.

(And, by extension, one of the reasons why “The Most Dangerous Game” is such an appealing scenario is because it ironically inverts the paradigm again by removing the safety of the game-space.)

But here we come to the crux of the matter: Are MMORPGs games? Or are they digital extensions of our social lives?

That’s obviously not a question with an easy black-or-white answer. MMORPGs create a complex shade of gray somewhere in the middle of that scale, and they create a natural conflict between people who have different opinions about how much they should be played as games and how much they should be lived as a social outlet.

Myers chose to define himself as an unrepentent blackguard: He vigorously approached City of Heroes as nothing but a game space and, thus, refused to acknowledge any aspect of the social aspect of the game. This conveniently placed him at the extreme end of the MMORPG scale, which meant that everyone else in the game was almost guaranteed to lie further towards the social end of the scale.

Which explains why, as one person quoted by Myers said, “everyone hates you twixty”.