Go to Part 1

So what does this all look like in actual play? Well, let’s simulate a campaign (with some actual dice rolls for stuff like the campaign’s starting town) and take a look.

For the purposes of this simulated campaign, let’s largely ignore the players being able to define their own scenarios. In actual play, this will almost certainly happen: Ten-Towns is enough of a living environment that the players can, for example, decide to become caravan guards from Kelvin’s Cairn; or re-open an abandoned inn; or buy mead from Good Mead to sell at a high price in a town where the taverns are running dry because trade has been disrupted. But what we’re going to focus on here is primarily just the baseline play that arises directly out of the sandbox structures in the campaign.

INITIAL STARTING QUEST: Cold-Hearted Killer

A dwarf named Hlin Trollbane believes she’s identified the serial killer who’s been plaguing Ten-Towns — it’s a man named Sephek who’s travelling with Torg’s merchant caravan. She approaches the PCs in a tavern and asks them to track the killer down and kill him.

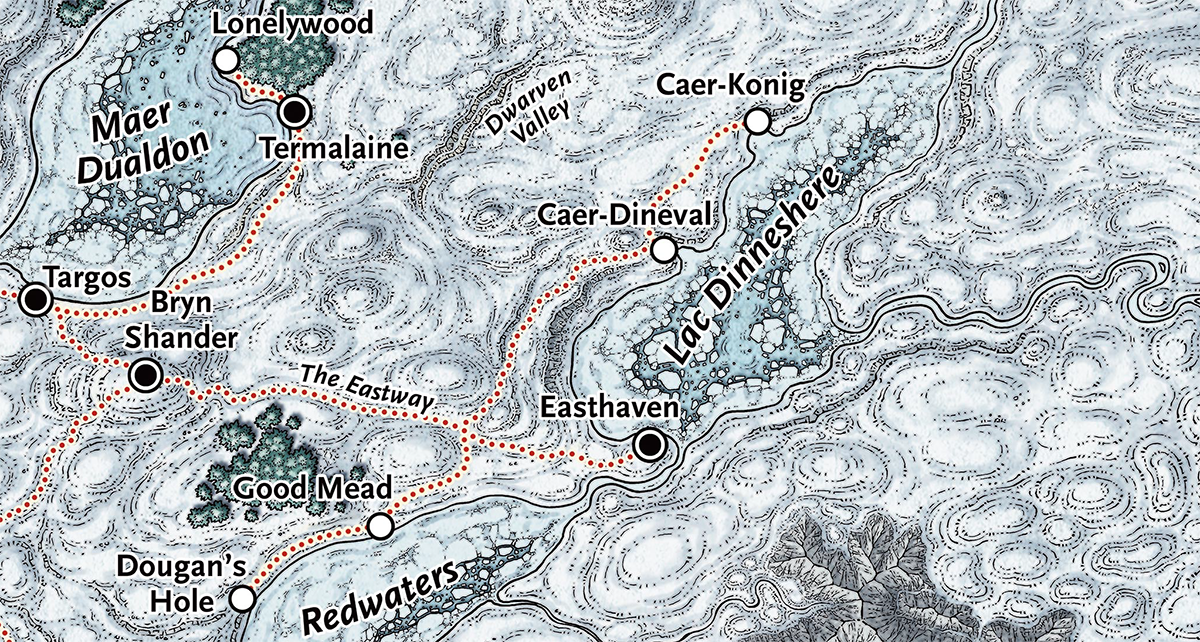

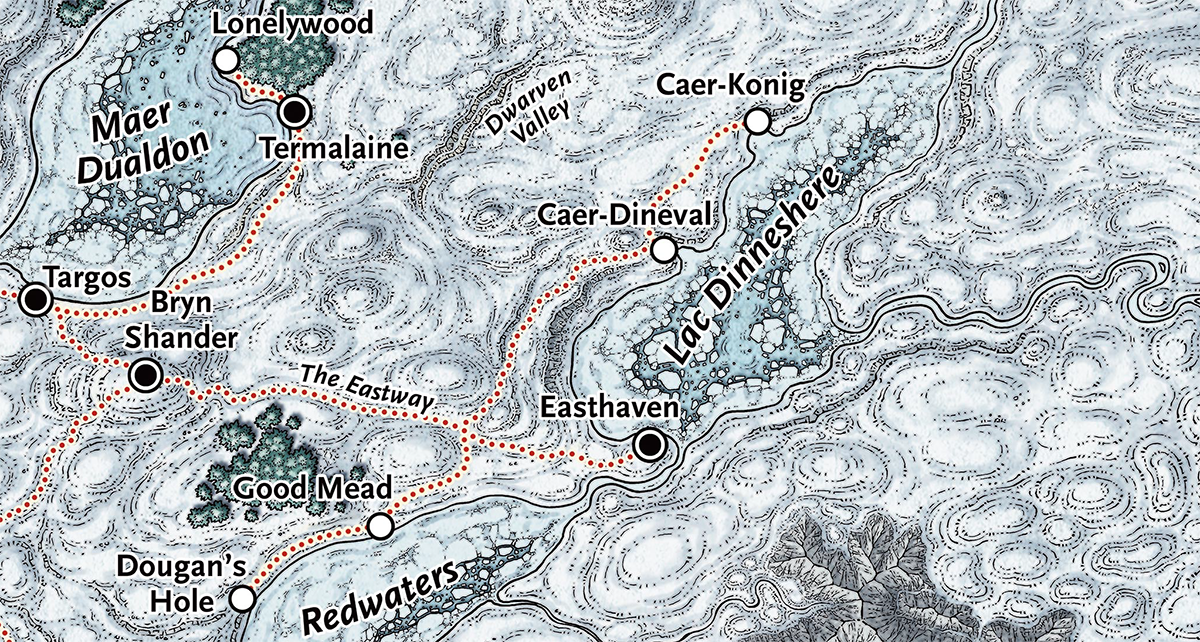

STARTING TOWN: Caer-Konig

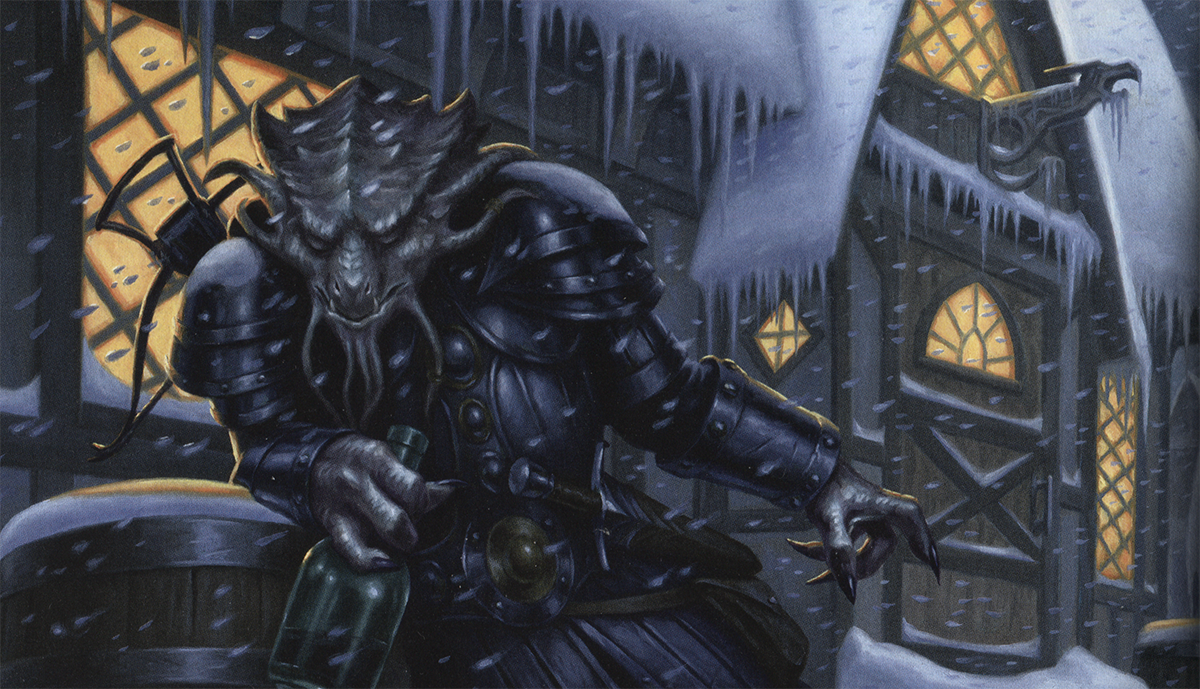

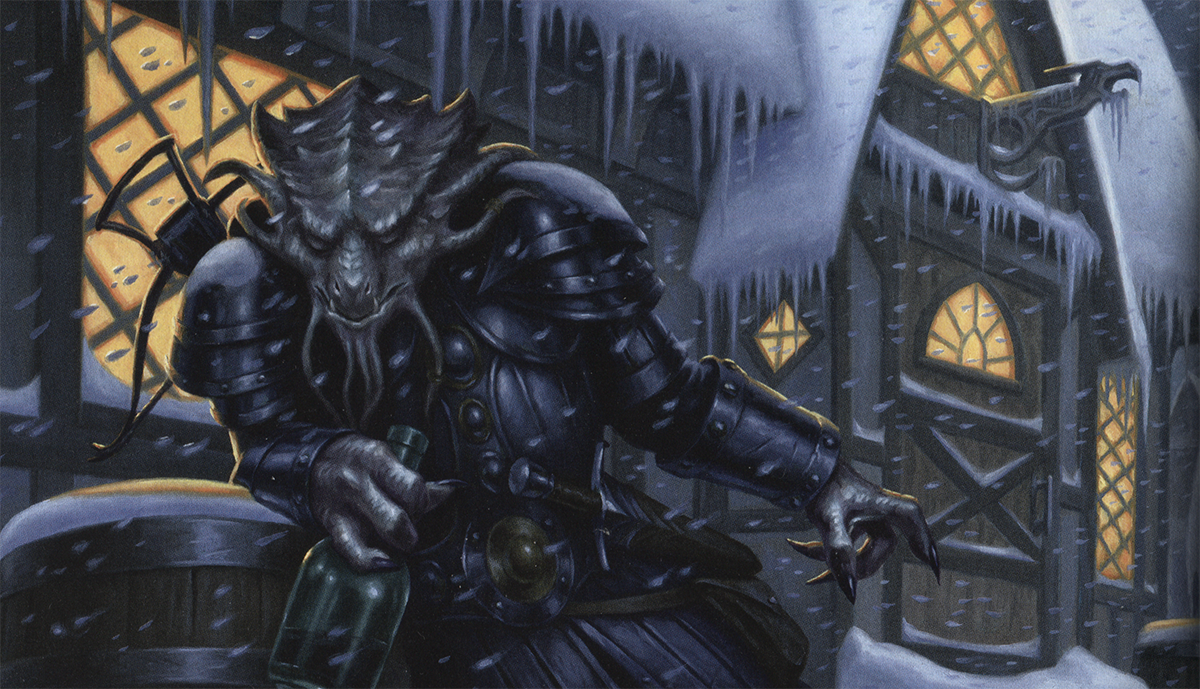

The quest in Caer-Konig sees the PCs stumble across Speaker Torvus, the dragonborn leader of the town who is drunkenly patrolling the streets in a vain attempt to capture dwarven thieves who have been sneaking into town. This eventually leads them to a nearby Duergar Outpost (p. 47).

Right off the bat here my instinct is to have the PCs enter Caer-Konig, encounter the drunken Speaker, and get the Duergar Outpost quest. When they get back to town (having leveled up to 2nd level), Hlin says, “I’m impressed. I think you might be able to help me bring a little more justice to this cold-blighted Dale.”

The success of the first quest diegetically justifies Hlin approaching them for the bigger job. I now roll to see which town Sephek will be found in.

SEPHEK’S TOWN: Easthaven

Alternative: If you wanted to more strictly adhere to the published structure (starting quest first!), the campaign starts in the Hook, Line, and Sinker (p. 46), where Hlin hires them to kill the serial killer. They leave the tavern and immediately stumble over Speaker Torvus, who leads them to the Northern Light tavern on the other side of the town and starts the Duergar Outpost quest.

STRANGE ALLIANCES

Either way, they head down the road and pass through CAER-DINEVAL.

Caer-Dineval is one of the towns without a proactive quest, so the PCs could just pass right through without getting one. But they’re looking for the serial killer, right? So they’re going to head to the local tavern, the Uphill Climb (p. 38), and start asking questions.

The adventure tells us that Roark, the proprietor of the Uphill Climb, won’t explicitly tell the PCs what’s going on in town (most likely out of fear), but he will try to point them at the caer (castle) in the hope that they’ll get involved. So when they start asking questions, he’ll say something like, “If any caravan was looking for permission to set up here, they’d inquire with the Speaker up at the caer.”

So the PCs head up there and knock on the door.

The caer has been secretly invaded by a cult called the Knights of the Black Swords that, among other things, wants to stop the duergar invasion of Ten-Towns: They’ve killed the guards, taken the Speaker hostage, and are ruling the town in his name. The way this quest works is that the PCs can bust up the cult and rescue the speaker, OR they can end up allying with the cult. The cult has some divine guidance which, if the PCs have taken any anti-duergar actions, will have informed the cult that the PCs can be useful allies and that they should go out of their way to accommodate them.

So if the PCs did the Duergar Outpost quest, then the likely outcome here is that the Black Swords form an alliance with them. (“Your coming has been foretold!”) That’s a second quest complete.

Alternative: If the PCs heard about the duergar thieves and said, “Doesn’t seem like our problem,” or if they tried to follow the duergar tracks, got lost, and never found the outpost, then when they go up to the caer to ask questions about Torg’s caravan, they’re simply told, “Nope, no Sephek here,” and turned away.

As the PCs head back down the hill from the caer, they meet Dannika Graysteel, who’s heading back from another disappointing attempt to find a type of fairy called a chwinga. This kicks off the SECOND STARTING QUEST — “Nature Spirits”, p. 25 — when Dannika asks them to look for chwingas in the other towns of Ten-Towns.

Now the PCs head down the road to where it intersects with the Eastway.

The choice of which way to go is now basically random. So, for the sake of argument, I rolled a die and determined that this hypothetical group is heading to GOOD MEAD.

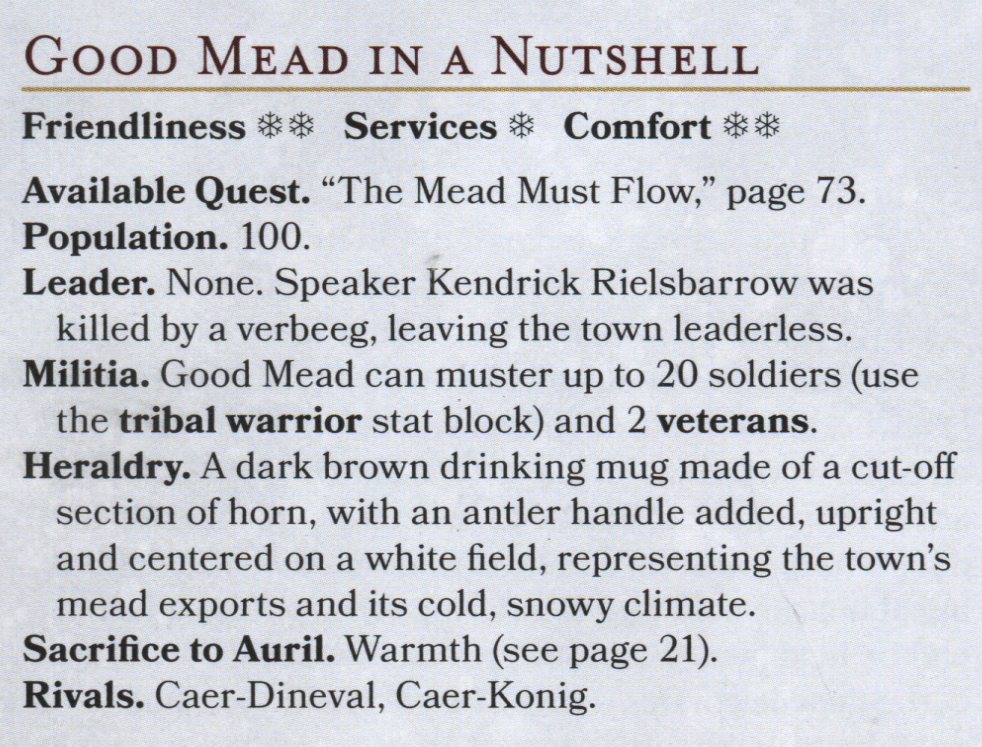

As they approach Good Mead, they encounter a trapper. They ask him about chwingas, but he shakes his head; he hasn’t seen any chwingas around here. (There’s a 25% chance each town has chwingas. I rolled a 47 for Good Mead, so no chwingas here.) But he does tell them that he just discovered five dead bodies out on the tundra. This is the quest hook for the Verbeeg Lair (p. 71).

These players, however, decide NOT to follow the trail from the dead bodies back to the verbeeg’s lair. Tackling a giant all by themselves just sounds too tough. But they want to do the right thing, so they gather up the bodies and take them into Good Mead for a proper burial.

In Good Mead they hear that the verbeeg has stolen the town’s mead supply and killed the Speaker, threatening to ruin the town’s economy. But this mostly just confirms that the giant is going to be too tough for them to handle.

SAVIORS OF GOOD MEAD

One of the PCs, however, decides to rally the townspeople: Alone they can’t stop the verbeeg menace. But together they can triumph!

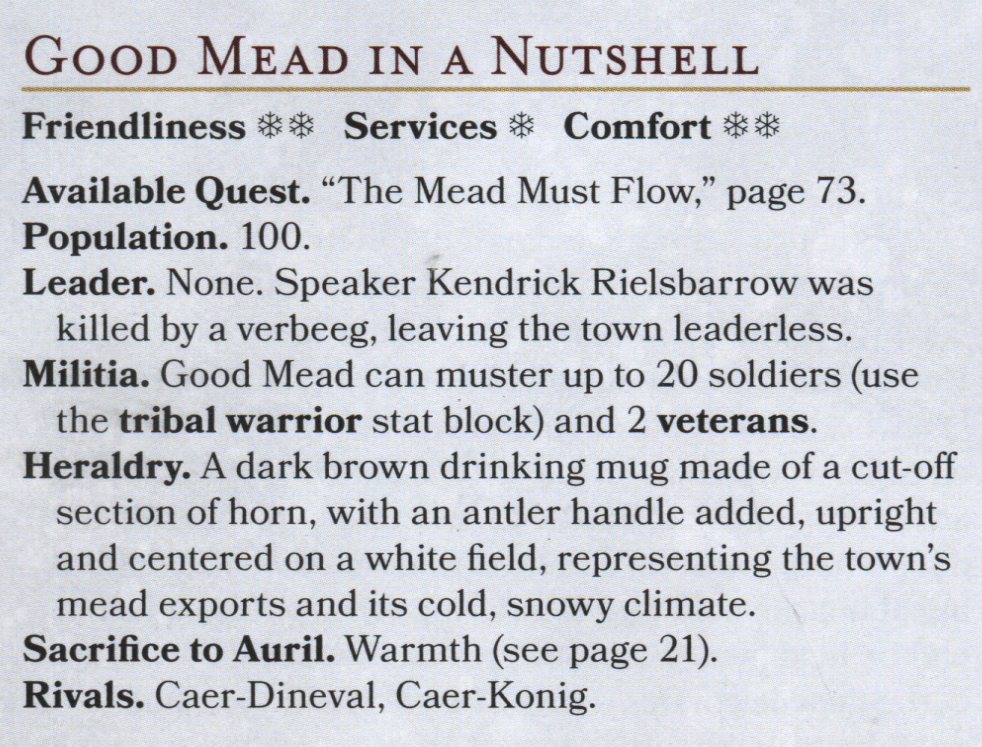

The stat block for Good Mead conveniently lists what the local militia can muster:

So the PCs make some solid Charisma checks and they rally two veterans and 10 tribal warriors to go giant-hunting. (If they’d rolled better, they could have perhaps gotten ALL the tribal warriors to go with them.)

On the way to the verbeeg lair, I frame a couple of scenes where they’re chatting with other members of the expedition. I use the opportunity to introduce Shandar Froth and Olivessa Untapoor (p. 78) and improvise a couple of new NPCs representing the common folk of Good Mead. During this small talk, the PCs also pick up two more rumors: Dwarves are having trouble bringing their goods to Bryn Shander due to yeti attacks. And Dougan’s Hole, down the road, is being plagued by a couple of dire wolves or awakened wolves or polar wolves or werewolves.

(Depends on who you ask and how tall the tale has gotten.)

Note: I’m deliberately inserting uncertainty and/or broader context into these rumors compared to the default text in the adventure. See also Random GM Tips: Surprising Scenario Hooks.

The giant-hunting expedition is a huge success. Maybe one of the group’s new NPC friends gets killed (a little pathos never hurt anybody). That’s another quest complete, so the PCs are now 3rd level.

The PCs return to Good Mead. While everyone is celebrating (and mourning), Olivessa Untapoor approaches them: Good Mead needs a new Speaker. A strong speaker. Shandar Froth thinks he should do it, but he’s a jackass. People are asking Olivessa to run against him, but she really doesn’t want the position. She thinks that one of the PCs should stand for the election.

Now, if the PCs want, this could totally happen! They’re the heroes of the hour. They’ve got the support of a major civic leader. There’s a whole thing where Shandar, regardless of who he ends up running against, pulls some shenanigans during the elections (p.78), but the PC candidate can probably end up on top.

This would, of course, change the entire nature of the campaign! Which is great! As the DM you’d need to come up with some civic challenges for the new Speaker (and their closest advisors; i.e., the other PCs) to deal with. You don’t have to completely abandon the existing toybox while you’re doing this, though. For example, you can look at the existing rumor tables and think about how to re-contextualize them to the PCs’ current circumstances.

For example, this rumor:

In Lonelywood, beware the dreaded white moose! It attacks loggers and trappers on sight, and the town’s best hunters can’t seem to catch or kill the beast. They could probably use some help.

We could easily imagine Speaker Huddle of Lonelywood sending a diplomatic mission to the newly ensconced Speaker of Good Mead: Having heard the success they’ve had with the verbeeg raider, she’s hoping they can send help to Lonelywood. In exchange, she promises to give Good Mead a discounted rate on Lonelywood’s lumber.

Or maybe it’s not Speaker Huddle. Maybe local loggers have lost confidence with her and have sent their people to extend a similar offer to the PCs. Maybe the PCs end up conspiring with the loggers to oust Speaker Huddle, with another of the PCs taking her place. Desperate times call for strong men, right? So maybe this whole thing ends with one of the PCs rising to become the new King of Ten-Towns… but at what cost to their souls? Maybe this is what the devil supporting the Knights of the Black Sword wanted to happen all along!

ON THE ROAD AGAIN

However this might turn out, we’ve clearly moved away from the baseline structure of Rime of the Frostmaiden. So, for the sake of argument, let’s say this doesn’t happen: Maybe the PCs just aren’t interested. Or maybe one of the PCs becomes elected Speaker, but the others decide to continue adventuring (with the player of the Speaker starting a new character; maybe picking up one of the NPCs who fought by their side against the verbeeg).

In any case, they continue down the road to DOUGAN’S HOLE. Here we have a scenario hook in which the white wolves plaguing the town meet the PCs on the road and try to lure them back to their lair (p.54). But the PCs, having heard about them in Good Mead, know not to trust them. They kill one of the wolves and the other one runs away (as described in the book).

Reaching Dougan’s Hill they’re told people have been kidnapped by the wolves, so they track the wolf that escaped, rescue the prisoners, and are now 3rd level. They also hear that there are adventurers in Targos planning an expedition to Kelvin’s Cairn.

But still no Sephek. And (I roll a 35) no chwingas, either. So they head back up towards the Eastway. They come back to the intersection and need to choose between Bryn Shander (where they’ve got a quest rumor) and Easthaven (where the killer has been known to operate).

It’s still a toss-up, in my opinion. Players could rationalize either choice pretty easily. (They might also head all the way back to Caer-Konig to see if there’s any chwingas there, but this seems like a marginal possibility to me at this point.) Rolling randomly, it looks like this hypothetical group is heading to BRYN SHANDER.

As they enter town, they’re approached by three dwarves who would like their help recovering a sled shipment of iron that they had to abandon during a yeti attack (p. 34).

The PCs do that, completing their fourth quest. They also pick up two more rumors at the Northlook Inn: Kobolds have invaded the gem mines of Termalaine. And people are also talking about how no one has seen the town speaker of Caer-Dineval for weeks now…

Huh. That’s weird, actually. The people in the castle were very nice, but now that you mention it, we never actually saw the Speaker did we?

CONCLUSION

At this point, I’m not sure what our hypothetical group will do next. Lots of options, though:

- Maybe they’re running low on coin and decide rescuing a gem mine from kobolds in Termalaine sounds profitable.

- They might double back to Caer-Dineval to check out what’s really going on with their “allies.”

- They might try to backtrack the goblins who stole the dwarves’ iron.

- Before leaving Bryn Shander they might stop by the local shrine to Amaunator and speak to a gnome tinkerer who asks them to check in on his friend who lives in an abandoned cabin north of Lonelywood (p. 33).

- Or they could just continue down the road to Targos, searching for fairies and serial killers.

There are a couple key things to note here:

First, looking over these events, you can see how easy it would be to end up with a completely different campaign. A different starting town; a different decision by the PCs; a different random die roll; a different moment of creative inspiration and everything is transformed. This is not just interesting and exciting, it is also empowering. The players can feel the difference, and it’s intoxicating.

Second, the level of emergent complexity that we see here — the event horizon beyond which you can have no clear vision of what the campaign will be — is inherent to true sandbox play. Do the PCs become political leaders? Run a tavern? Become security guards for a logging consortium? Start a trading company? Mount archaeological expeditions to explore giant ruins? There’s no way to know and only one to find out!

(This is also why Rime of the Frostmaiden collapsing the sandbox of early levels into a more-or-less linear plot at the middle levels is rather disappointing. At the very point that the limitless potential of the sandbox begins to truly explode, the book instead says, “Okay. That was nice, but let’s lock it down.”)

If nothing else, I hope you’ve seen here that there’s nothing magical or even particularly difficult about running a sandbox campaign: After the sandbox has been filled with a selection of simple toys (some NPCs, some dungeons, some bad guys), all you have to do is observe a fairly simple procedure and follow the players’ lead, responding to their actions by picking up the appropriate (or most convenient) toys and actively playing with them.

Go to Icewind Dale Index